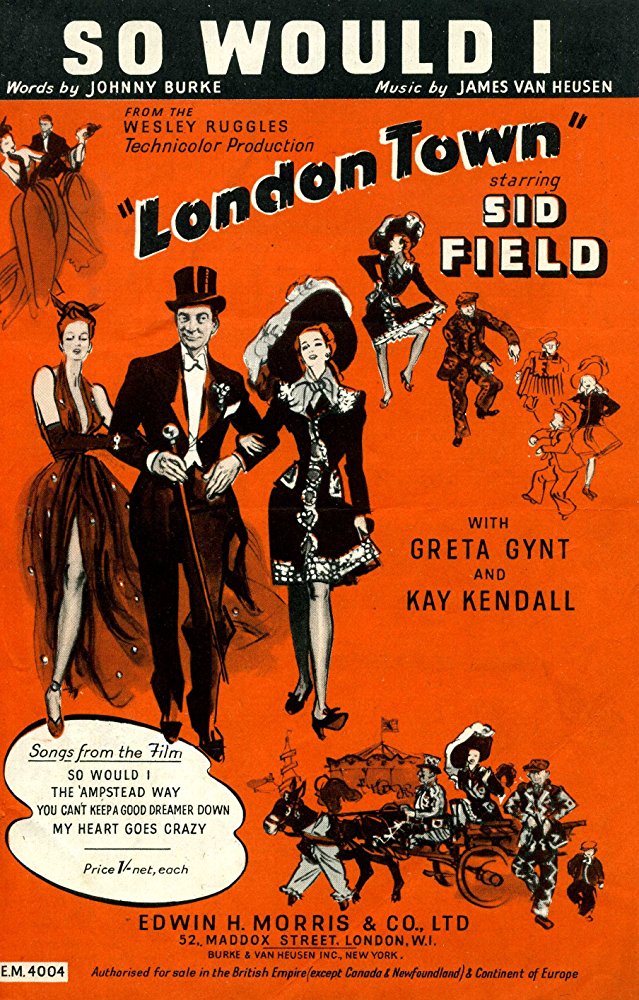

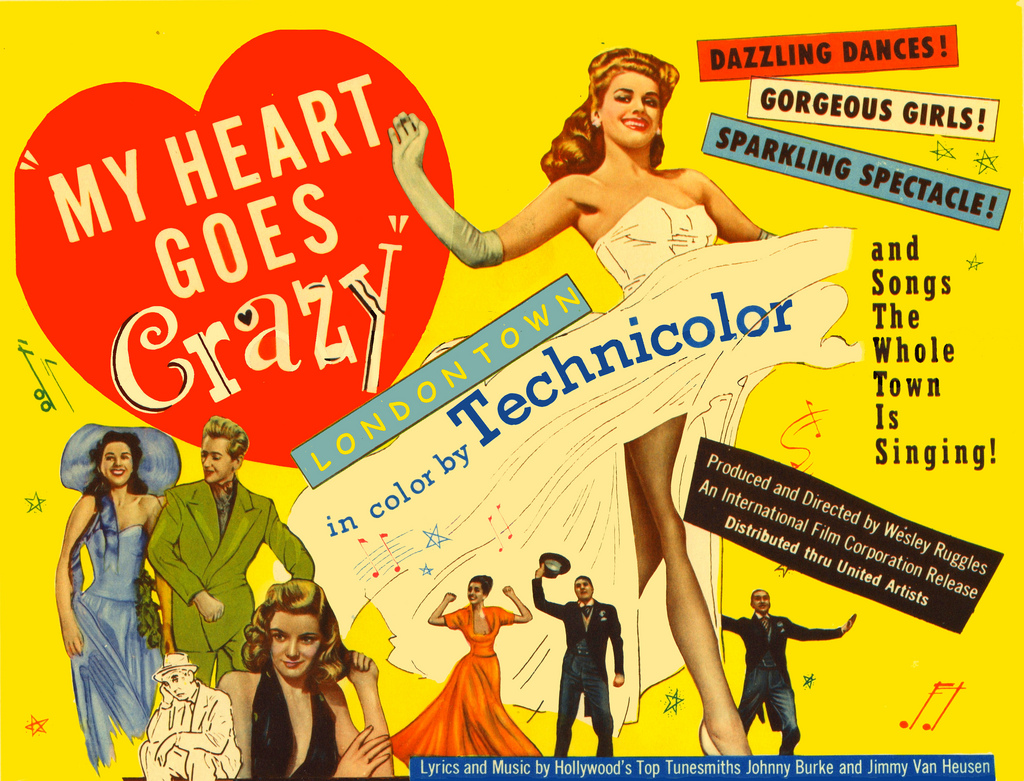

Taking advantage of his new-found fame as the great new British star, the comedian Sid Field was signed up as lead in a comedy/musical film to be called London Town to be shot in Technicolor at Shepperton Studios in the autumn of 1945. J. Arthur Rank was convinced that what the glamour-starved country needed and wanted most was a big, bright million-dollar musical. At great expense, the songwriters Jimmy Van Heusen and Johnny Burke were hired, and Rank imported the American director Wesley Ruggles to take the musical’s helm. It was an odd choice, as Ruggles had no experience with the genre, and his best-known movies, the Oscar-winning Western epic Cimarron and the Mae West comedy I’m No Angel, were both more than a decade old.

The screenplay revolved around a comedian, Jerry Sanford (played by Sid Field), who arrives in London believing he has been hired as the star of a major stage production, when in fact he’s merely an understudy. Thanks to his daughter Peggy (Petula Clark, at the time just thirteen), who sabotages the revue’s star Charlie de Haven (Sonnie Hale), he finally gets his big break. The premise allows for a variety of musical numbers and comedy sketches performed by, among others, the musical hall star ‘Two Ton’ Tessie O’Shea but also Kay Kendall in her film debut. Unfortunately it wasn’t an auspicious start to her career.

London Town, artistically and financially, has gone down in history as a disastrous failure. The Observer, for instance, thought the film had ‘all the sparkle of cold gravy and the taste of a cold in the head’. J. Arthur Rank had been wrong. The public may have been glamour-starved but they failed to turn up, both in Britain and the US (where the film was eventually released as My Heart Goes Crazy). The hoped-for rebirth of the British musical came to a screeching halt. Wesley Ruggles sloped back to America and never directed again, while Field’s film career was essentially over almost before it had begun. Kay Kendall, at nineteen, was hardly singled out for the film’s failure however the brash, hopeful publicity about ‘Britain’s Lana Turner’ certainly didn’t help her early career and she was soon dropped by Rank. ‘Nobody had ever heard of me but they called me a star,’ she later recalled. ‘I opened bazaars, signed autographs, went to premieres, did everything a star was supposed to do. My photograph was on magazine covers and front pages of newspapers. And all before we’d even finished the picture.’

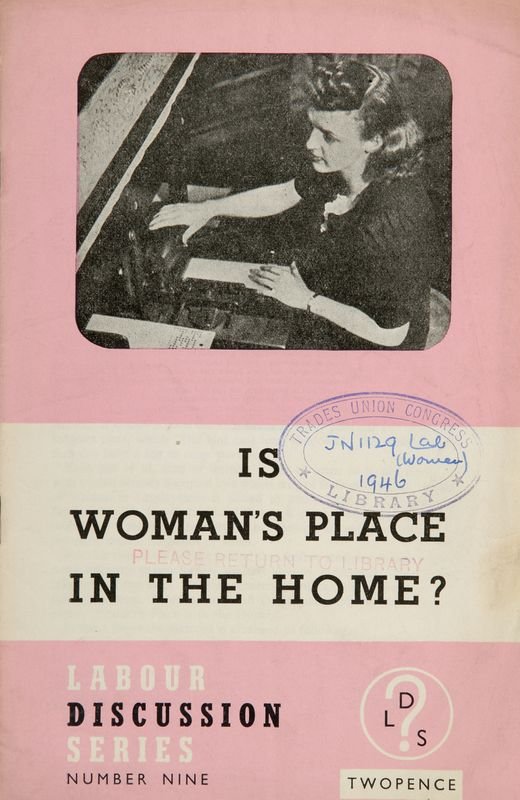

A Rank executive, Kendall later claimed, although she didn’t name him, called her into his office to release her. ‘You are a very ugly girl,’ she recalled him saying. ‘You have no talent. You are too tall and you photograph horribly. Find some nice man and get married.’ In 1946 telling a young woman to go and get married meant, euphemistically, it was time to give up your career. It is worth noting that it wasn’t until October 1946, the month after London Town was released, that the Civil Service marriage bar was abolished – a ruling that prohibited married women from joining the Civil Service and required women civil servants to resign when they became married (incredibly, the marriage bar for the Foreign Office wasn’t lifted until 1973). In 1947 there was a government enquiry into the end of the marriage bar, with one senior official writing: ‘To us, married women have been, to quote the Treasury – “a perfect nuisance”.’ Another recorded: ‘Naturally, their home comes first with them, and if their husbands or children are ill, they regard it as their duty to remain at home and look after them, especially in these days when nurses and domestic help are almost unobtainable.’

The Rank executive who released Kendall was an idiot. She was tall and beautiful, with a delicate turned-up nose and a purr for a voice. She was also funny – very funny. She was born in Withernsea in 1926 – her grandmother, the music hall star Marie Kendall, along with Max Miller and Gracie Fields, performed at the Palladium in the Royal Variety show in 1931. Nine years later, when she was just thirteen, her granddaughter Kay was tall enough for the Palladium chorus line and eventually became one of the students in the Rank charm school. She grew up to be, as the film critic David Thomson described her, ‘not just a beauty, but one of the most sophisticated-looking women you had ever seen’.

After the disaster of London Town, Kendall almost disappeared but for small parts in Jules Dassin’s Night and the City and Dance Hall and Lady Godiva Rides Again both with Diana Dors. In 1953 her luck changed when she appeared in the charming comedy Genevieve about the annual London-to-Brighton vintage car race. The film, a huge hit in the UK, showcased her perfect comic timing not least in the very funny dancehall scene where she joins the band and, much to the surprise of her friends (and the band), plays a brilliant jazz trumpet. At last her talent where she somehow remained elegant and classy even while performing pratfalls or comic drunk scenes, was appreciated.

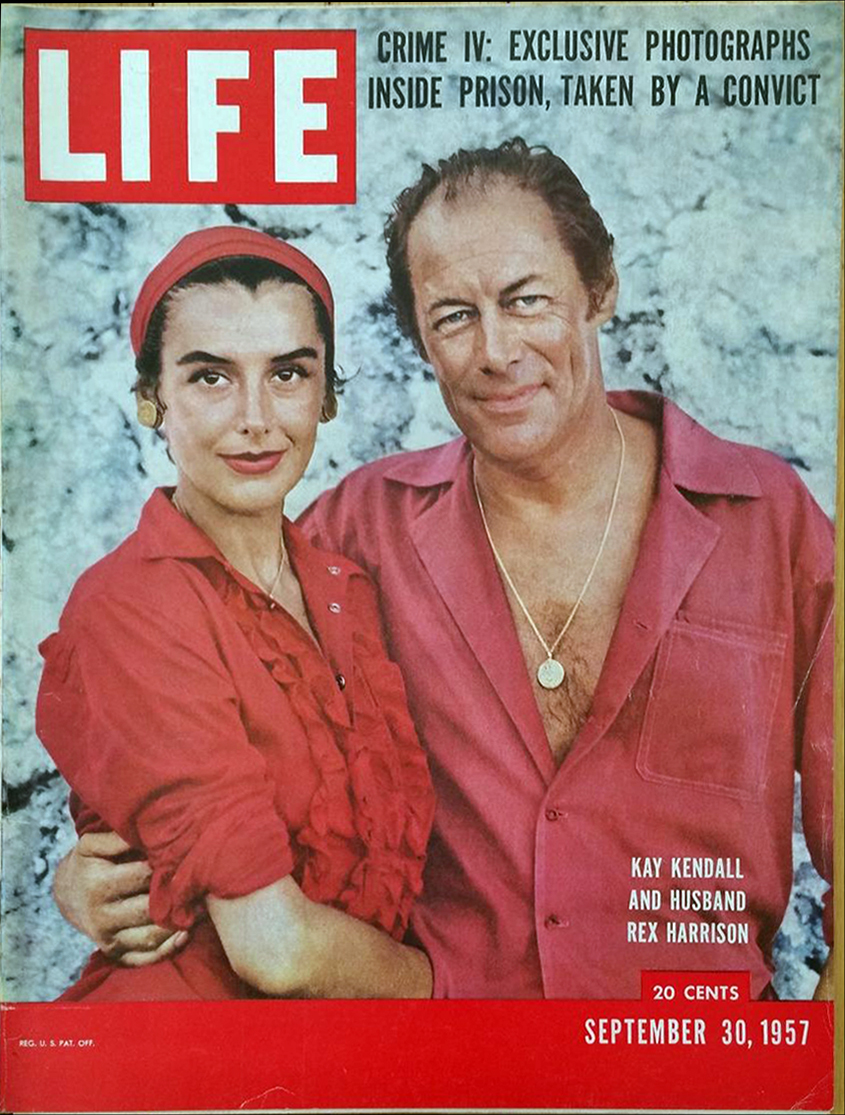

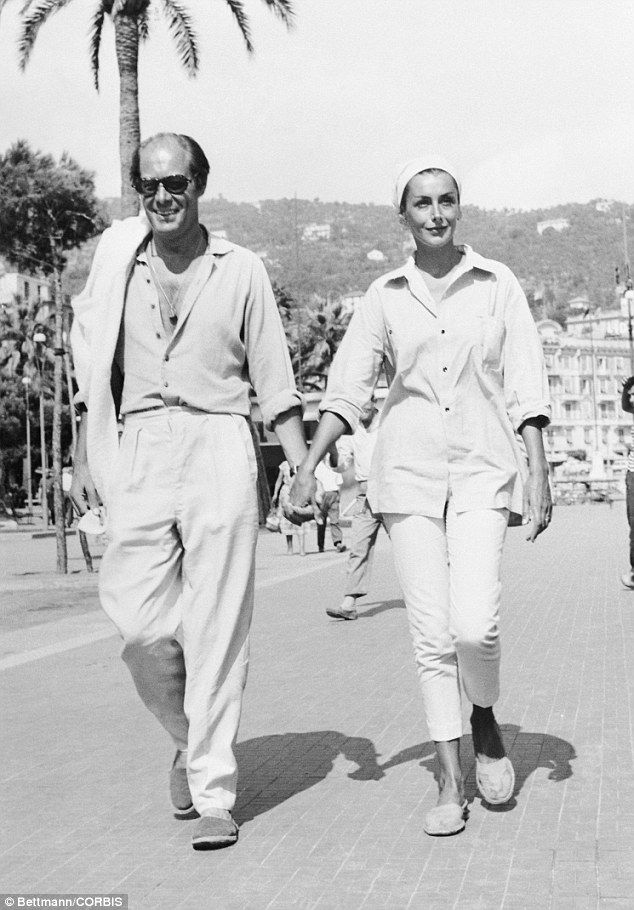

In 1956 Kendall began an a air with Rex Harrison after they had both appeared in The Constant Husband. They married the following year, but not before Harrison was called in by Kendall’s doctor, who told him that she had fatal leukaemia. With the collusion of the doctor, Harrison took it upon himself to keep it a secret from Kay who thought she was suffering from an iron deficiency. In Sheilah Graham’s “Hollywood in Person” column on July 14, 1959 she wrote:

The rumors that Kay was suffering from leukemia are untrue, fortunately.

“I’m anemic and have a blood ailment, but I’ve gained weight and feel much better,” said the piquant comedienne…”

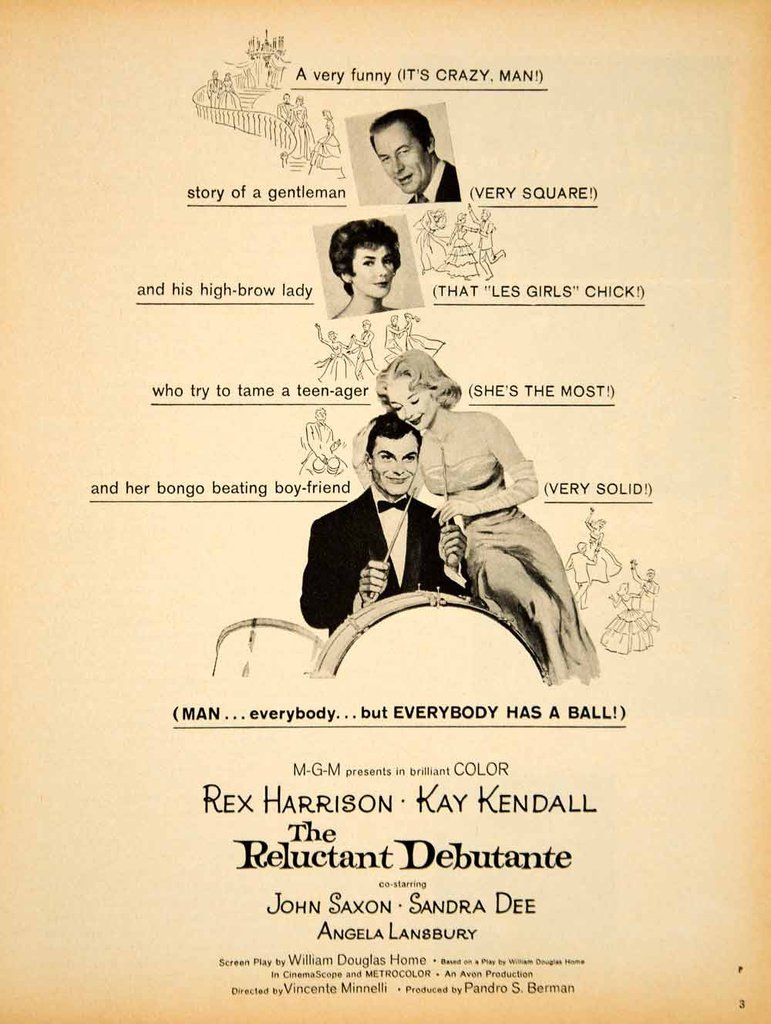

In 1958 Kendall won a Golden Globe Award for her performance as Lady Sybil Wren in Les Girls – the story of three showgirls in postwar Paris (with Mitzi Gaynor and Taina Elg). The following year she starred opposite Harrison in the comedy The Reluctant Debutante.

Rhoda Koenig in The Independent wrote in 2006, “As they say about crime victims, Kay Kendall was in the wrong place at the wrong time. In her case, the crime was a waste of talent. One of the most delightful of British actresses […] few of her films gave her a chance to shine. A natural screwball heroine, Kendall was born too late for the 1930s comedies in which she would have been the equal of the scatty but scintillating Carole Lombard or Claudette Colbert, and too soon for the naughtiness and absurdity of the 1960s.

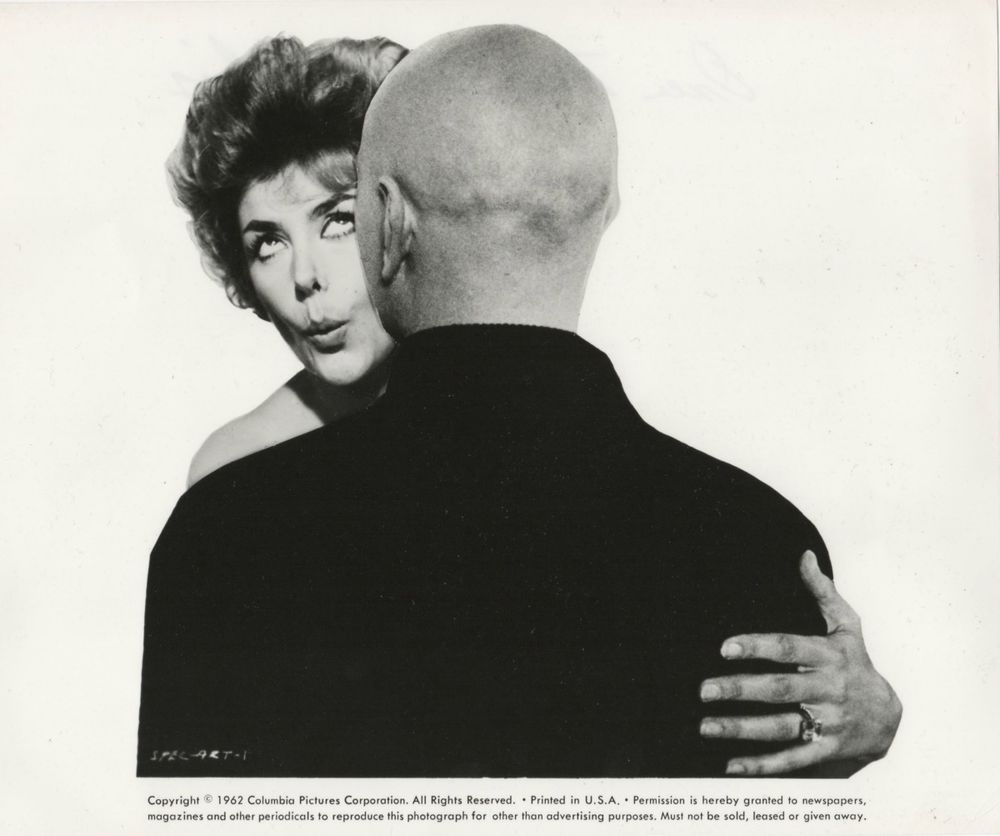

Kay Kendall died in 1959 aged just thirty-two and not long after completing the comedy Once More, with Feeling! where many people say she stole the film from her co-star Yul Brynner, who played her conductor husband.

This is a short excerpt from Rob Baker’s book High Buildings, Low Morals.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.