British Leyland Chairman Lord Donald Stokes and Minister of Transport John Peyton at the International Motor Show at Earl’s Court, London, 25th October 1972. Photo- George W. Hales

Derek Robinson who the tabloids loved to call ‘Red Robbo’ referring to his Communist sympathies, was a name synonymous with the ignominious failure of Britain’s largest car manufacturer. In fact the company was badly run almost from the start and many of its problems had been obvious in the companies that were brought together to form the huge enormous conglomeration that made up British Leyland. And then, as soon as the company seemed it could be on the right track along came the oil crisis and the three-day week.

When Sir Donald Stokes was given the role of turning around of what was practically the entire British-owned car industry in 1968, the Financial Times described it as “the toughest job held by any boss in Britain.” With the encouragement of Anthony Wedgwood Benn MP (plain Tony Benn wasn’t until 1973), as chairman of the Industrial Reorganisation Committee, the former engineer and salesman became the chief executive of British Leyland Motor Corporation (BLMC) formed with the merger of Leyland Motors (which owned Triumph and Rover) and British Motor Holdings (BMC), which owned Austin, Morris, MG and Jaguar. On the night of the merger somebody asked Stokes if any thought had been given to dropping the rather uncool ‘Leyland’ from the new title. The Leyland Truck and Bus Company, of which Stokes had been chairman, had a long history dating from 1896, when the Lancashire Steam Motor Company was formed in the town of Leyland in North West England. Irritably, Stokes, despite being born in Plymouth and educated in Devon, snapped back at the assembled Press: ”Certainly not. Don’t lets have any of your bloody-minded Southern attitudes here.’

It seems incredible now but immediately after World War Two Britain was the world’s largest manufacturer of motor vehicles and proud of famous names such as MG, Austin, Morris, Jaguar, Rover and Rolls-Royce all of which were seen as symbolic of the country’s engineering expertise and manufacturing strength. Within twenty years Britain had been overtaken not only by the US but also France and Germany. The Wilson Labour Government thought that further amalgamation of the British car companies might be a way of getting back on track. The idea was to produce an ‘industrial conglomerate able to produce more than a million cars a year – allowing it to properly compete with the American-owned Ford and Vauxhall.

The Leyland truck and bus company which had moved into cars with the acquisition of Standard-Triumph and the famous Rover brand concentrated on the low-volume upper end of the market and had remained relatively successful. Whereas BMH (a product of an earlier merger between the British Motor Corporation, Pressed Steel and Jaguar) in the late sixties was very close to a complete collapse. The company was a sprawling mess in almost every way imaginable, largely as a result of the mishandled Austin/Morris merger in 1952. At that time Austin boss Leonard Lord had boasted: “You know what BMC stands for? Bugger My Competitors!” In one way he was right, but the only buggering that BMC (and subsequently BMH and finally British Leyland) did was to themselves. The myriad of famous and historical marques could not help but compete with each other and the ageing model range the new company inherited suffered from far too much duplication.

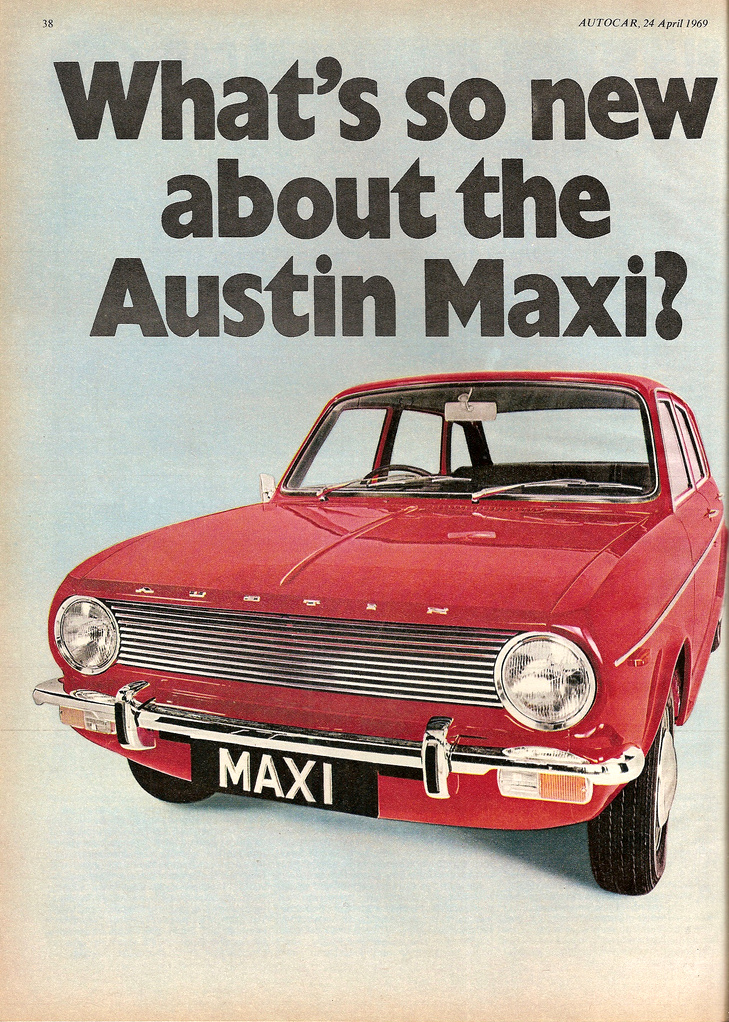

Sir Donald Stokes’ company statement at the end of 1968 ended with the words, “The world is looking to see whether British Leyland can match up to the international challenge. I believe it can – the future potential of the corporation in enormous.” A few months later Stokes emphasised this enormous potential by introducing Leyland’s first new car by saying ‘the new Austin Maxi is not one of those crappy cars with exotic styling and no room in the back and that date before you can get them into reverse’. He continued: ‘the undated style is more important than beauty that is only tin-deep’. The Guardian reported that the man from Ford said, “Let’s be realistic. Stokes has put as good a face on an inheritance as he could.’ And indeed Stokes had been shocked that BMC only had the Maxi and the Mini Clubman undergoing serious development and coming close to anywhere near ready.

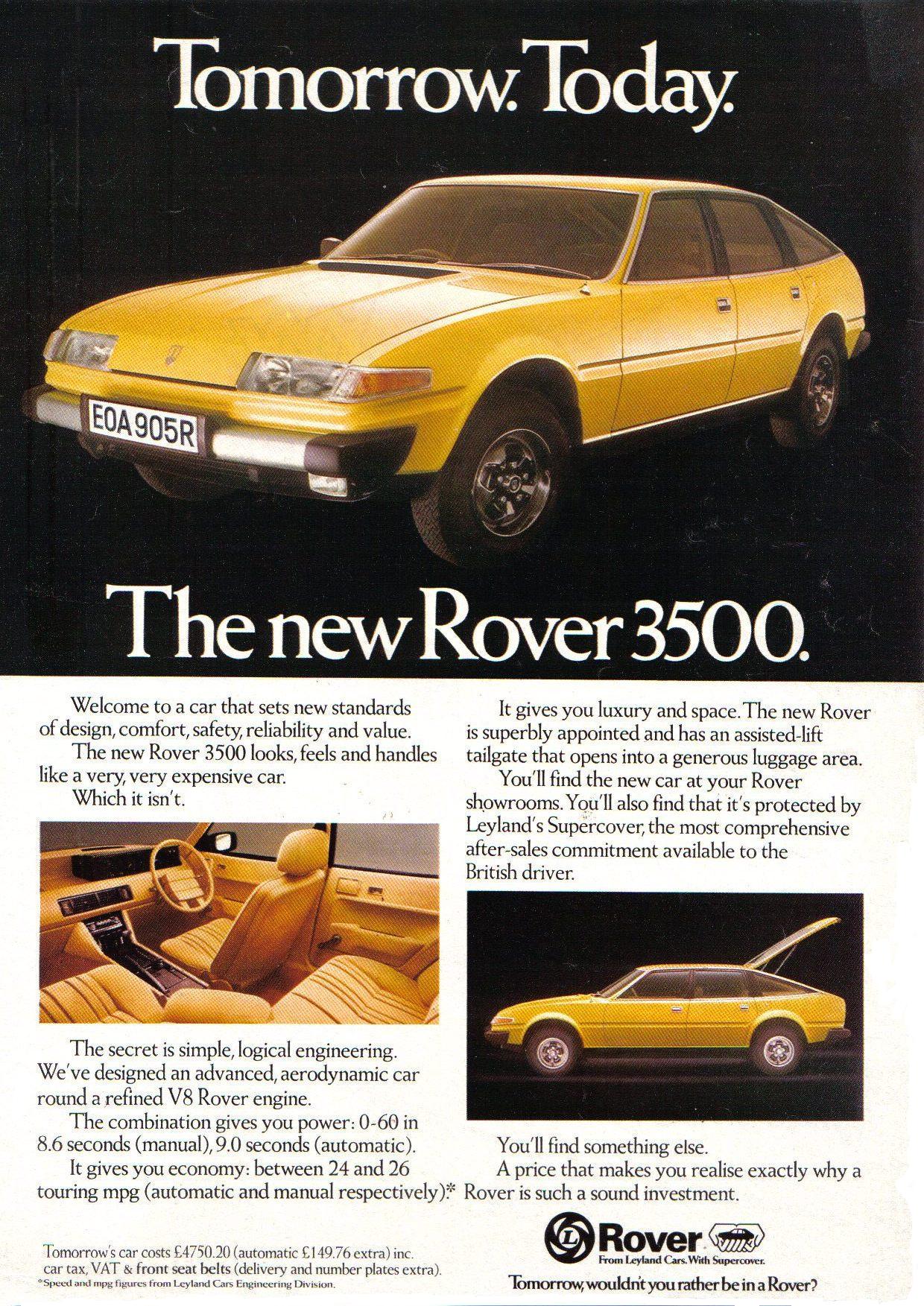

Austin Maxi Ad from April 1969. The Maxi (code name ADO14) was the last car designed under the British Motor Corporation (BMC) before it was incorporated into the new British Leyland group, and was the last production car designed by famed Mini designer Alec Issigonis.

The Austin Maxi

The Austin Maxi was underdeveloped and had an odd appearance hampered by using the doors from the larger Austin 1800. It was spacious and comfortable, however, and had five doors and boasted five gears (“All the Fives” said the advertising). All good but unfortunately its quality and reliability were severely lacking. The gear change was atrocious, the engine was weak and breakdowns were more than commonplace. It was soon found to rust appallingly. Between 1969 and 1981 production totalled 472,098 but today only about 150 remain in existence. The Maxi was the first line in what’s been called the longest suicide note in industrial history: the death of the British car industry.

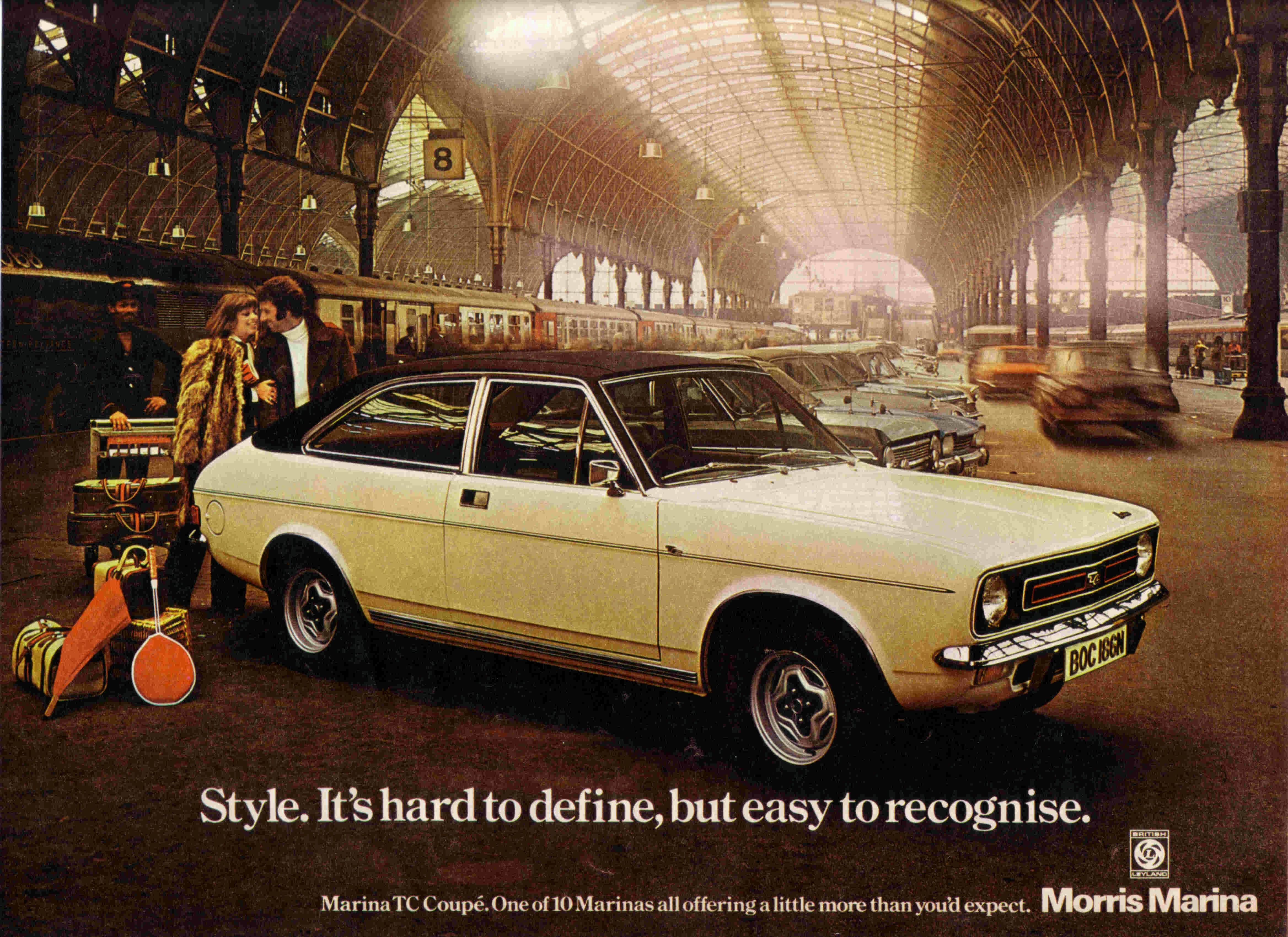

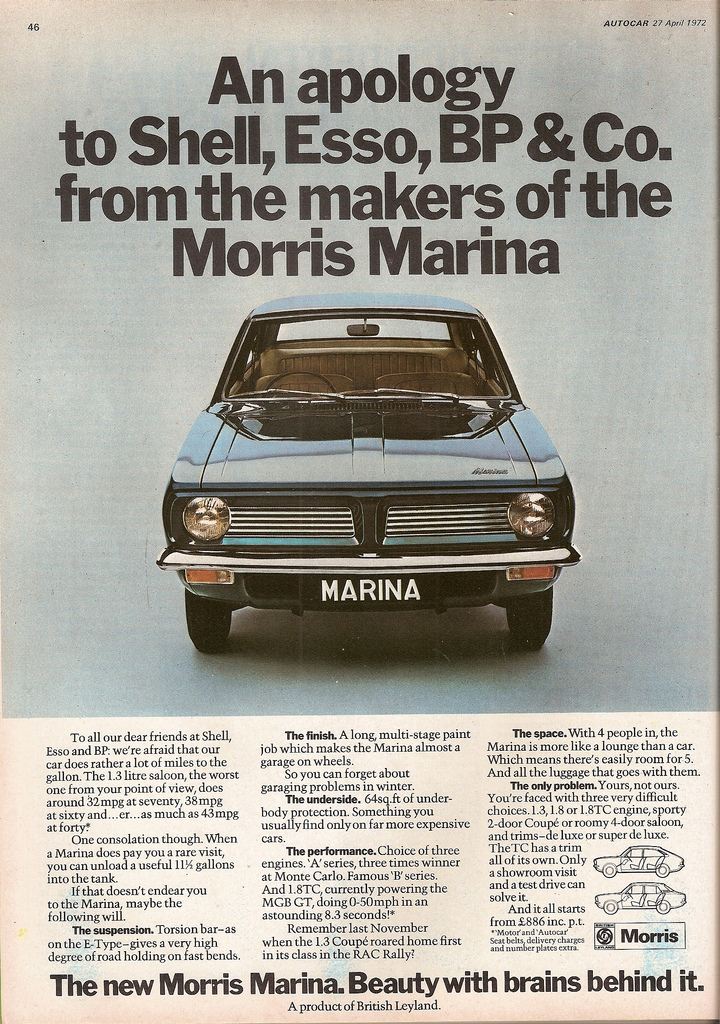

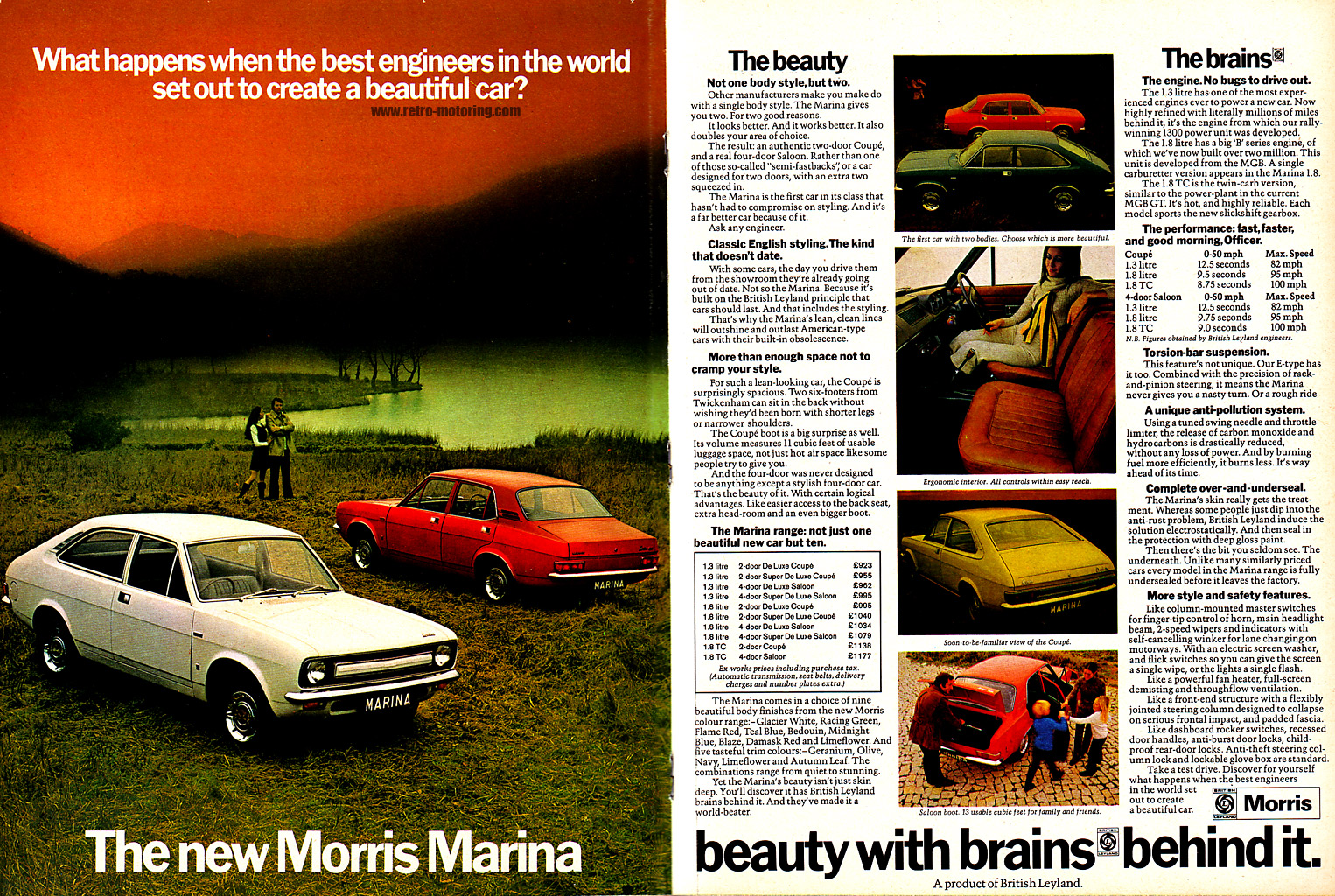

The Morris Marina

When the Marina was launched in 1971 it was conceived as a simple car that would be easy to service and cheap to run – perfect as a fleet car to rival the Cortina. The development was rushed (bosses demanded it had to be ready for the 1970 Earls Court Motor Show), however, and to save money it used components from the extraordinarily ancient Morris Minor. Harris Mann, a designer at Leyland, would later write: “It was identified that all the [British Leyland] front-wheel-drive cars were losing money and the Escort wasn’t losing money – which was how the Marina came about,” Mann explained. “It wasn’t built to rule the world, it was just meant as a simple car that used odds and ends from around the corporation – which is just what Chrysler was doing and it got them out of a hole at the time.”

The Marina had always been planned as a stop-gap but when the time came for a replacement the company was bankrupt – and the Morris had to soldier on with a few minor modifications. When the Marina 2 went on sale in 1978 Motor magazine concluded: “Dated suspension, crude handling, mediocre roadholding, poor driving position – way behind its competitors.” Andrew Roberts in the Daily Telegraph wrote of the Marina: throughout much of its life it suffered from an affliction common to far too many British cars of that era – total contempt for the customer.

Even the upmarket version managed to give drivers the overwhelming sensation that they were worthless paupers; the “carpeted boot” of the 1.8 Special had all of the opulence of a badly fitted lavatory mat.

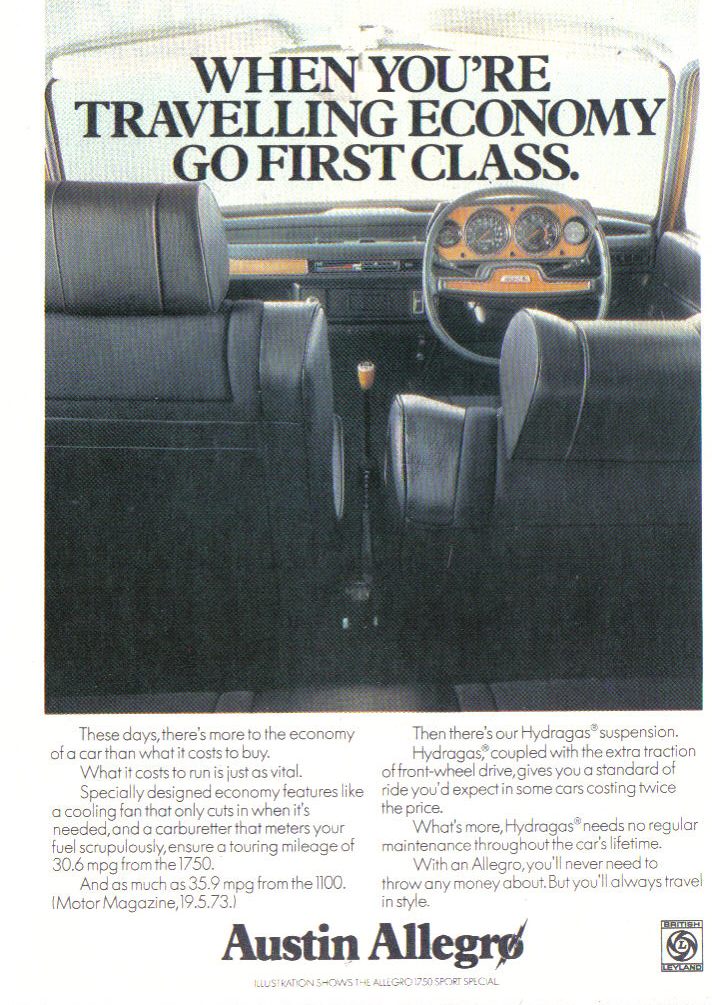

The Austin Allegro

The Allegro was launched in 1973 designed by Harris Mann and still infamous for its ‘Quartic’ (or square) steering wheel. Unlike the Marina, always seen as a stop-gap, the Allegro was always meant to be a major contender. It would have been a good-looking modern car if the designers weren’t constrained by bulky engines and outsize heaters (because of parts sharing). The odd square steering wheel came from the engineering department where they thought it would give more leg room and an ability to see the instruments. It was actually sold as a safety aid by Leyland as it meant the driver had to hold it properly! Needless to say, the Quartic was got rid of in less that a year. Quentin Wilson writing about the Allegro in the Mirror (in 2008 it was voted as the worst car ever) maintained that the, “villain of the piece was Lord Stokes, head of British Leyland, who insisted on using seats from the Maxi and trim from the Marina, and spoiling Mann’s visionary design.”

The Allegro other than the gear-box had relatively good reviews when it came out in 1973. Car magazine was especially complimentary. Stories of rear windows that fell out if you jacked up the car in the wrong place and wheels falling off did not become common criticisms until much later. The car was actually banned from the Blackwall tunnel as dangerous to tow, because their shells would bend and back windscreens pop out.

Although almost 600,000 Allegros were made there are only 180 left on the road.

Derek ‘Red Robbo’ Robinson

Derek Robinson was a union man the tabloids loved to hate. His first job in the motor industry was as a 14 year-old apprentice at Austin in Longbridge near Birmingham during WW2. He would join the Communist Party ten years later (he stood as a Communist candidate in four consecutive General Elections in Birmingham, Northfield between 1966 and 1974, but lost his deposit on each occasion, only managing to receive over 1% of the vote once, in 1966 – and was national chair of the Communist Party of Britain for a period in the 1990s) and the Amalgamated Engineering Union (AEU).

In 1975 British Leyland became bankrupt and was nationalised by the Government. At this time Robinson was the union convener of the Longbridge plant in Birmingham, having worked his way up from the shop floor to serve as the deputy of the previous convenor, Dick Etheridge, a fellow member of the Communist Party. With his network of representatives in the 42 different Leyland plants around the country, he led a long-running campaign of strikes around the company which he argued were in protest at mismanagement.

Robinson was eventually sacked by BL in November 1979 for putting his name to a pamphlet that criticised the BL management. More than 18,000 BL workers immediately went on strike in protest of the sacking while Robinson claimed that he was being singled out for opposing company policy in the past. A secret ballot on a strike in sympathy of the man by now known as ‘Red Robbo’ and opposed to the dismissal was held in February 1980 but the motion not carried, votes being 14,000 against a strike and only 600 in favour. With headlines such as “Get lost Robbo” and “the man we can do without”. A local midlands newspaper suggested that Mr Robison should march off to Moscow to spend as much time as he liked swapping “Commie cant with his Marxist mates.” Robinson said the following day that, “A vicious campaign conducted both inside and outside the plant had led to a situation where it was difficult to get a appositive result. I am disappointed to lose my job not be doing anything wrong but by opposing the dictator, Michael Edwardes…our members have taken the wrong decision. They will live to regret it.”

A Tory party the following week described Robinson as a gnat on the back of British Leyland. The communist convener agreed with this and took the analogy further “If British Leyland was a horse then he was not only a gnat but was actually biting the jockey (a common shopfloor term for the BL chairman, Sir Michael Edwards) who was whipping an underfed and beleaguered nag the wrong way round the racecourse. Edwardes acknowledging that the removal of Robinson was in some ways necessary for the company’s preparations to bring the new Austin Metro into production. Longbridge was being substantially redeveloped and expanded for the new car, whose assembly was heavily automated in comparison to previous models and job losses would have been inevitable: “It was planned only in the sense…well, the answer is ‘Yes’, from a strategic point of view we knew that we couldn’t have the Metro and him. Whether or not we wanted him to go, his actions made it inevitable that he would have to go”

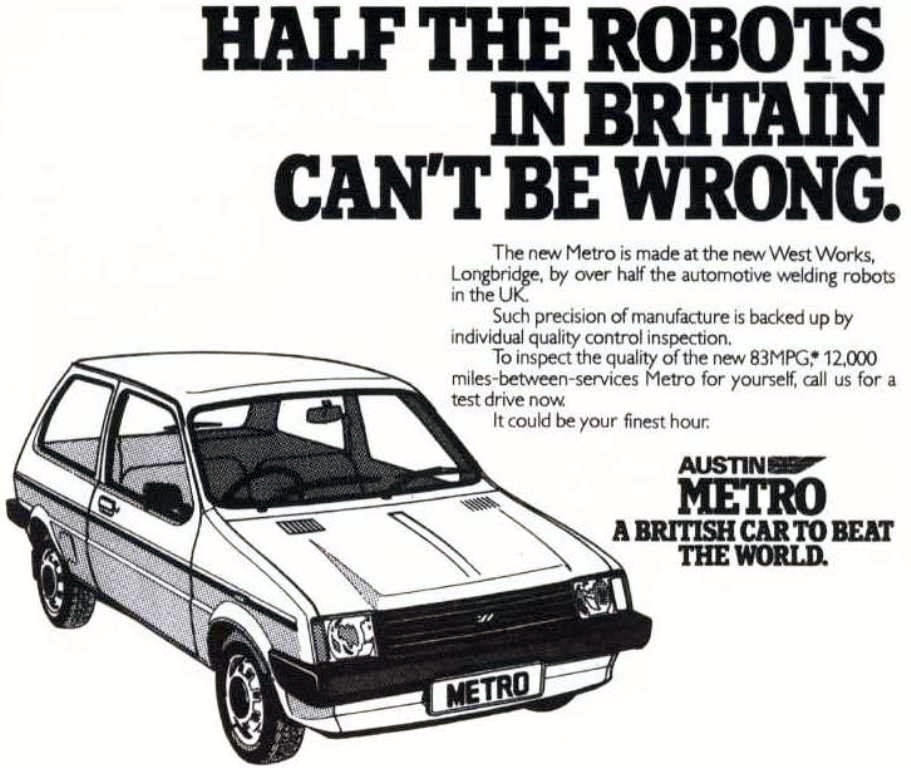

With ‘Red Robbo’ now out of the picture the Austin Metro was launched in October 1980. It was incredibly the first new model to come out of Longbridge for seven years, but also notable for the utilisation of modern robot technology to produce it.

In 1986, with the name British Leyland or BL as it was now known, only having connotations of everything that was bad about British industry, the company changed its name to Rover Group in 1986. This meant that the last vestiges of British Leyland were banished forever. Although it would literally take decades to wipe British Leyland and everything it stood for from the British consciousness.

In 1988 Margaret Thatcher’s government sold their unwanted shareholding in Rover Group to British Aerospace. It really was the end of British Leyland.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.