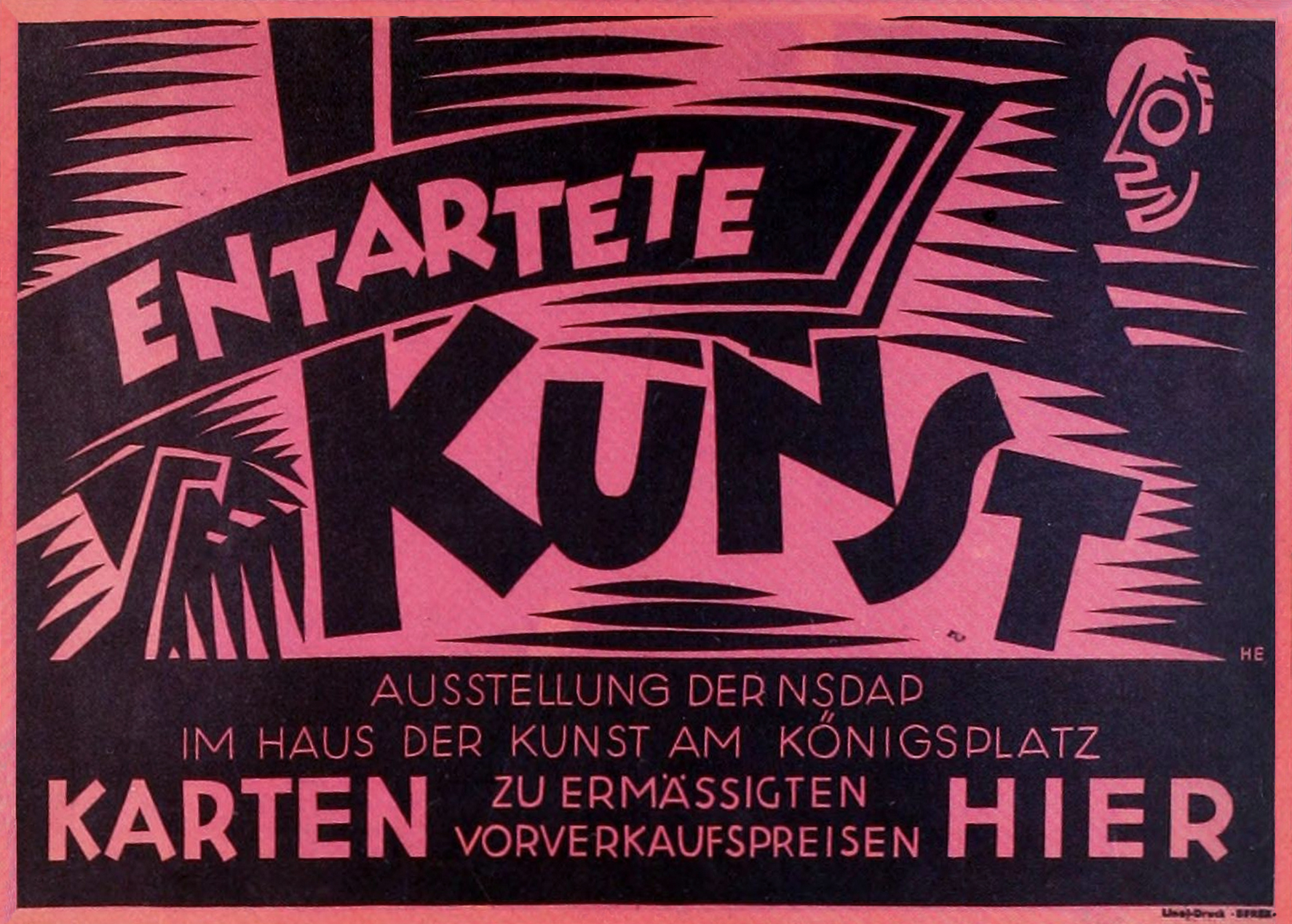

Poster of a 1938 exhibit in Dusseldorf

“If you have to ask what jazz is, you’ll never know,” said Louis Armstrong. The Nazis knew what it wasn’t. It wasn’t was the sound of their type of freedom.

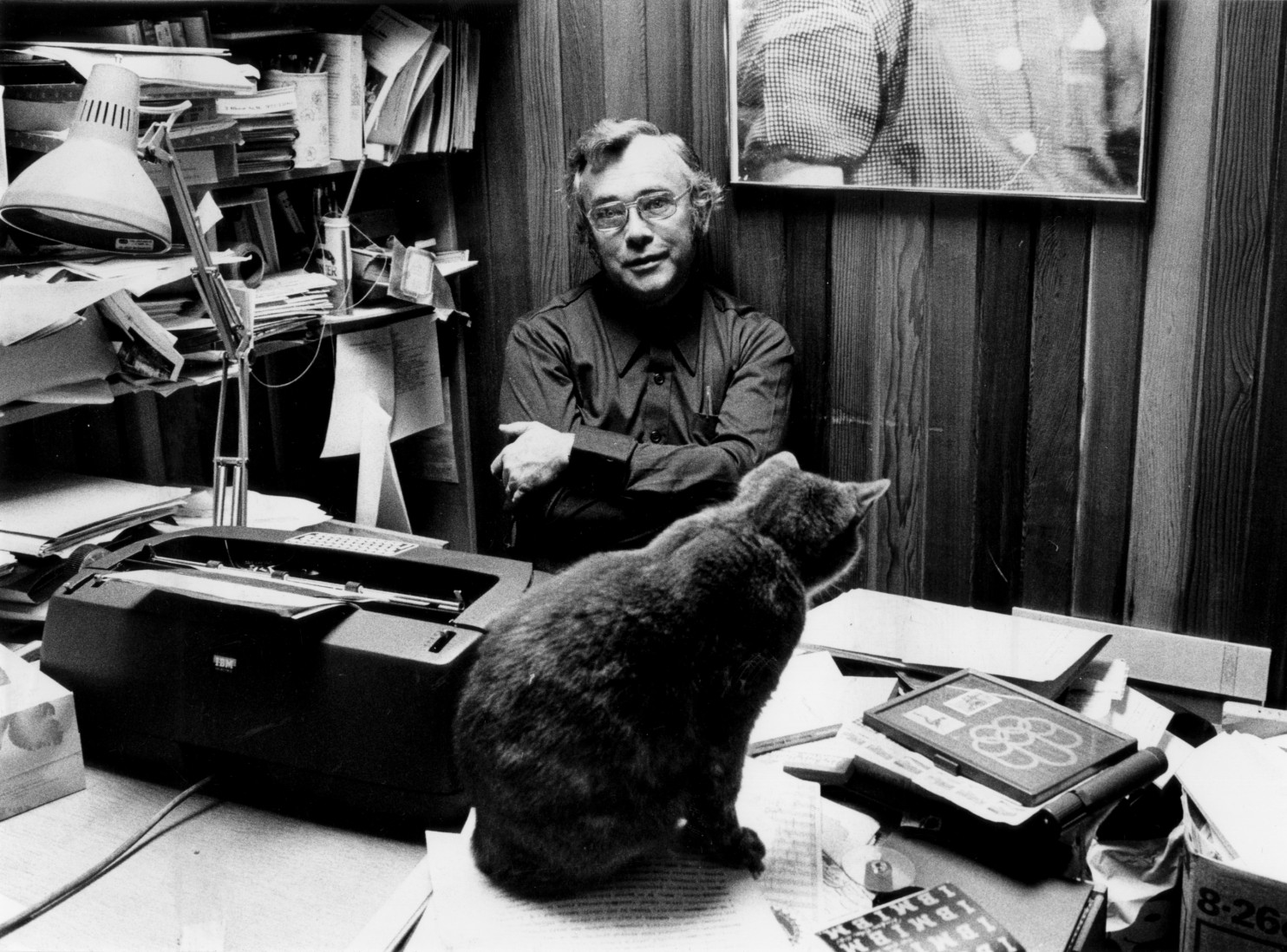

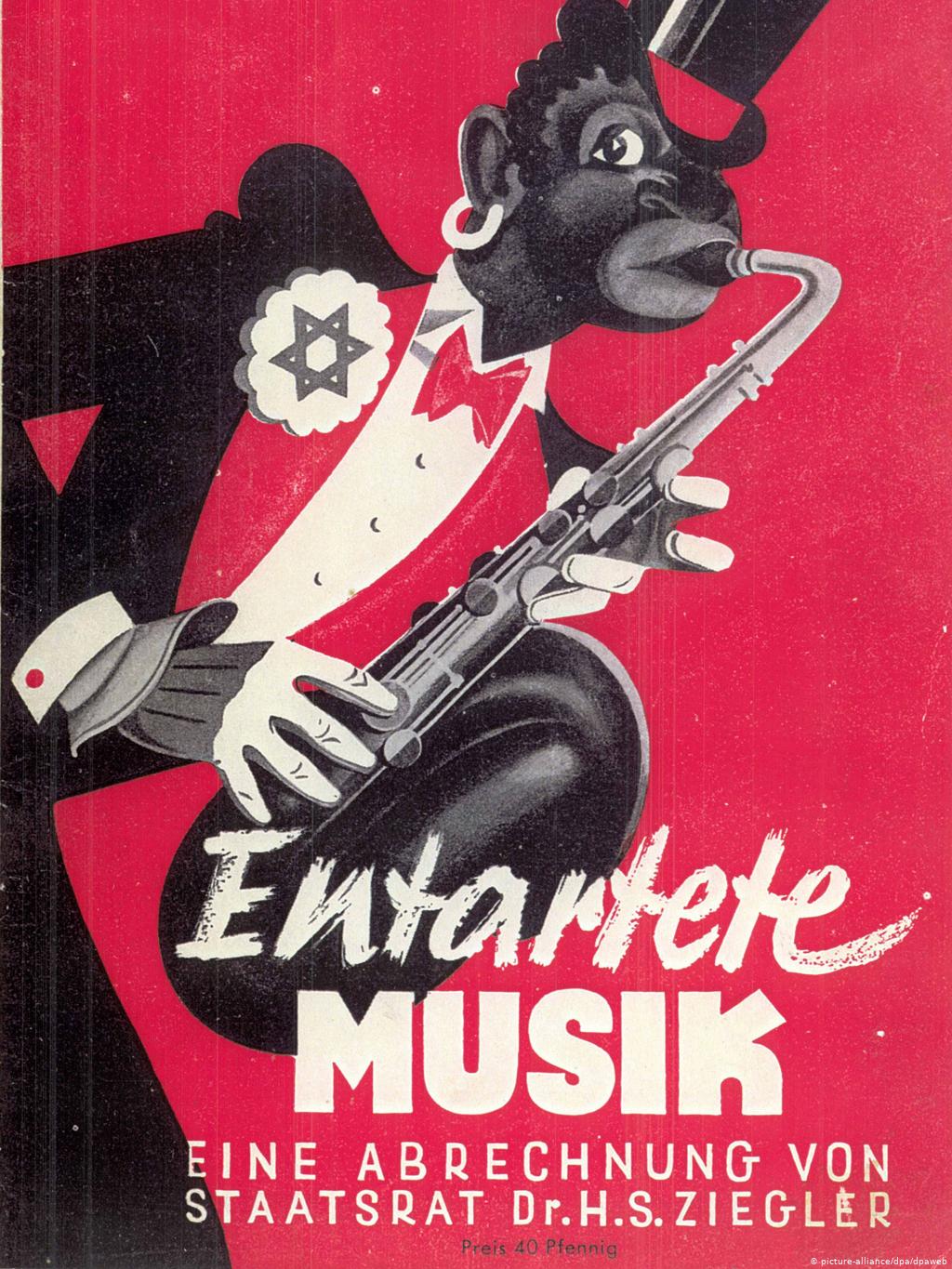

Josef Skvorecky (September 27, 1924 – January 3, 2012), the Czech writer, played the tenor saxophone (like his totalitarian-fighting hero Danny Smiricky in The Cowards and other books). When the Nazis invaded Czechoslovakia, Skvorecky experienced their “control-freak hatred of jazz”. To like jazz was to violate their law. Jazz was entartete musik (“degenerate music”), or as Nazis spin doctor Joseph Goebbels put it, jazz was “jungle music”.

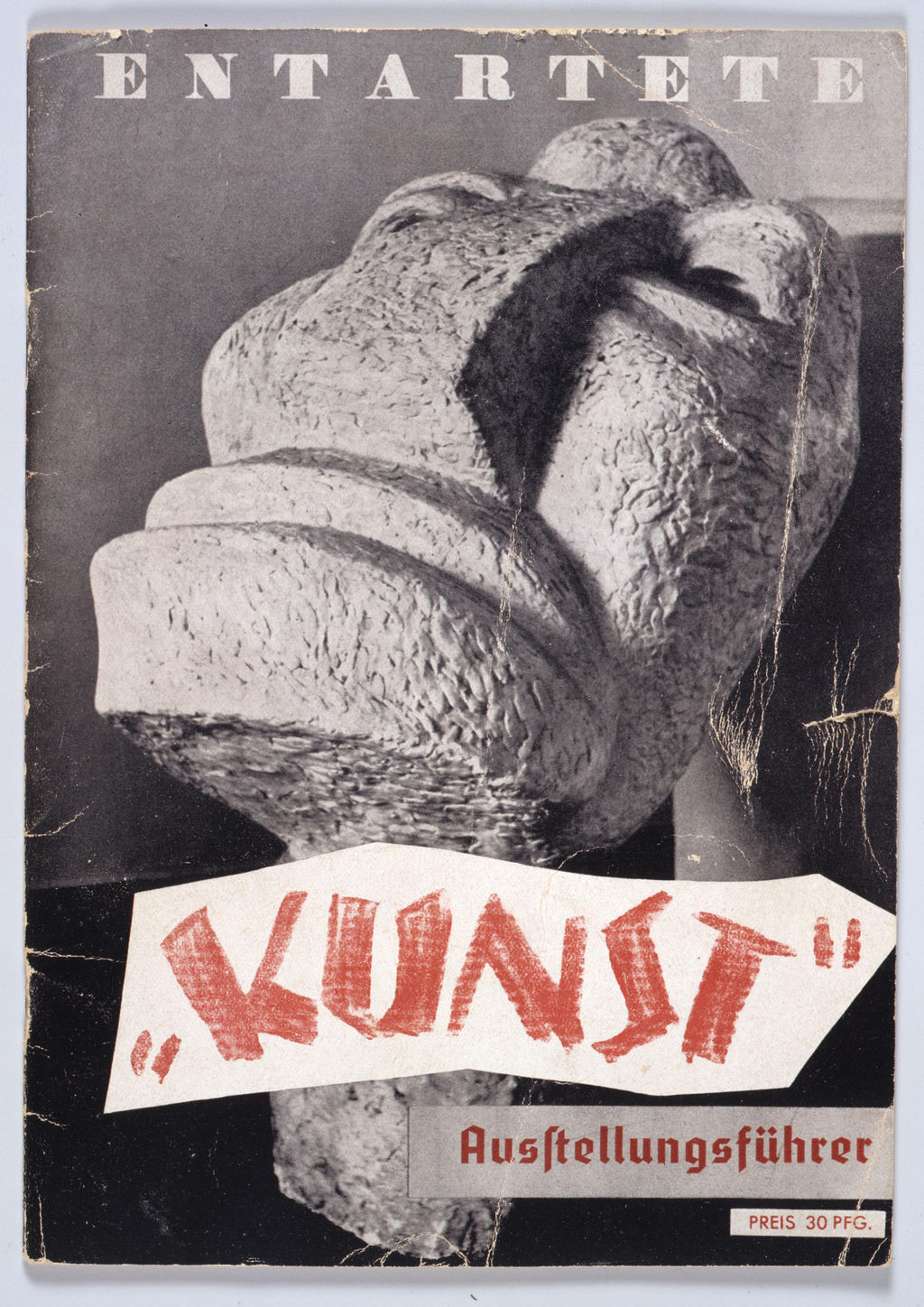

To press the point home, a travelling exhibition entitled ‘Entartete Kunst’ opened in Munich in 1937, displaying works deemed to be “an insult to German feeling”. How the Ubermensch flocked to be disgusted. More than two million visitors attended the exhibition from July 19 to November 30, 1937, in Munich alone.

Visitors look at works in the Degenerate Art exhibition in Munich, which opened on July 19, 1937. Pictured are Lovis Corinth’s Ecce homo (second from left) and Franz Marc’s Tower of the Blue Horses (wall at right), next to Wilhelm Lehmbruck’s sculpture Kneeling Woman. (via)

Guide to the exhibition “Degenerate Art”, 1937

The “Degenerate Art” exhibition building in Berlin, 1938

Entartete Kunst poster, Berlin, 1938

Such was the world Josef Skvorecky found himself in. He explains his love of jazz and how the Nazis hated it the introduction to his novella The Bass Saxophone:

In the days when everything in life was fresh — because we were 16, 17 — I used to blow tenor sax. Very poorly. Our band was called Red Music, which in fact was a misnomer, since the name had no political connotations: there was a band in Prague that called itself Blue Music and we, living in the Nazi Protectorate of Bohemia and Moravia, had no idea that in jazz blue is not a color, so we called ours Red. But if the name itself had no political connotations, our sweet, wild music did; for jazz was a sharp thorn in the sides of the power-hungry men, from Hitler to Brezhnev, who successfully ruled in my native land.

Jazz stood for more than just soul, sex, expression and harmony. Jazz was the American way. “I wanna show that gospel, country, blues, rhythm and blues, jazz, rock ‘n’ roll are all just really one thing,” said the sublime Etta James. “Those are the American music and that is the American culture.” And if the Nazis want to ban your culture, boy, are you doing something terrific.

“She forgot the definition of ‘jazz’ as well, “writes David Sedaris in Squirrel Seeks Chipmunk: A Modest Bestiary, “and came to think of it as every beautiful thing she had ever failed to appreciate: the taste of warm rain; the smell of a baby; the din of a swollen river, rushing past her tree and onward to infinity.”

In 1935, the Nazi government did not allow German musicians of Jewish origin to perform any longer. The Weintraub Syncopators – most of whom were Jewish – were forced into exile.

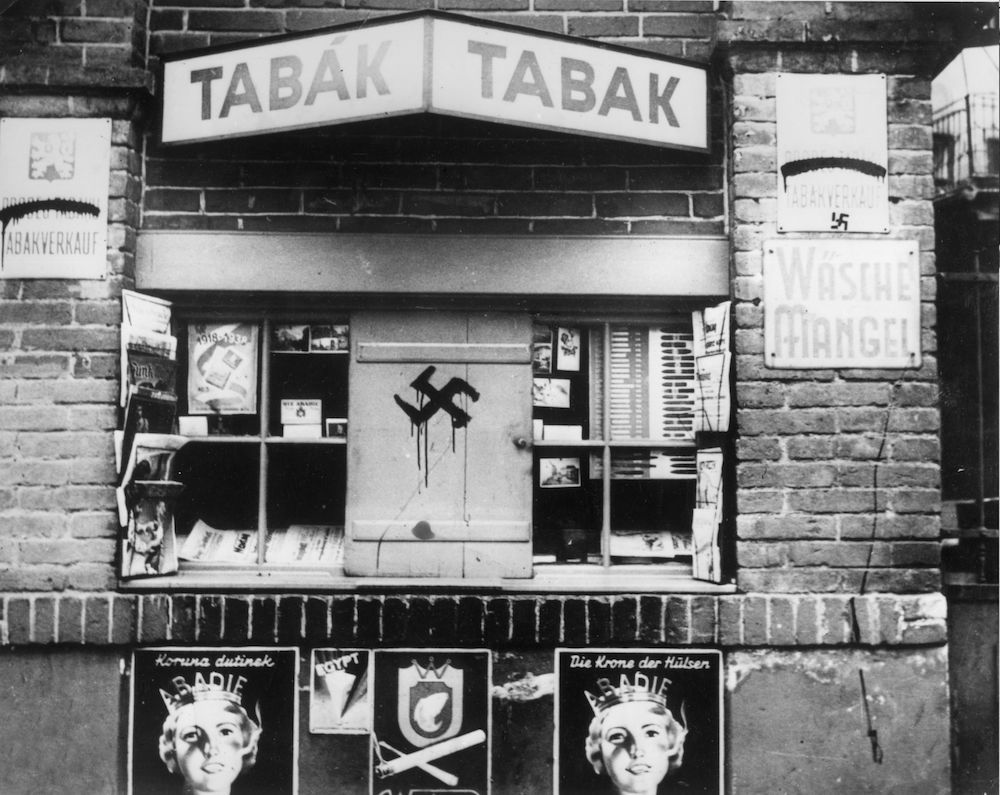

September 1938: A swastika painted onto the shutters of a ‘tabak’ or tobacconist in Teplitz, Sudeten Germany. This German-speaking region of Czechoslovakia was ceded to Germany in the Munich Pact of 1938, after which Czech writing was obliterated from the bilingual street signs, leaving only German text.

Skvorecky understood the importance of free expression, something banned by the Nazi and the Communists that followed. In 1980 he was awarded the Neustadt International Prize for Literature. In his address at prize giving, Arnost Lustig (21 December 1926 – 26 February 2011), a fellow Czech émigré author and Holocaust survivor, opined: “In a country that has not had any democracy for over forty years now, books like those of Josef Skvorecky have become forbidden fruit on the one hand, and a hope for dignity and freedom on the other.”

“I always wanted to be a jazz musician, and was really never much of one,” Skvorecky said in 1989. He recalled the catalyst of his love:

There was a Chick Webb recording called I’ve Got a Guy, which featured Ella Fitzgerald. At the time I didn’t know it was Ella, because most records then didn’t list the names of the singers; the showcase was the band. That was around 1938, when Ella was twenty. I’ve Got a Guy also had a wonderful saxophone chorus, and when I heard it for the first time, I thought I was listening to the music of the heavenly spheres, and I still think that.

So much for the background. Now for those rules to combat jazz. Ten of them were decreed by a Gauleiter, a regional Nazi official, during the Czech occupation. The list was printed in the introduction to the aforementioned The Bass Saxophone:

Pieces in foxtrot rhythm (so-called swing) are not to exceed 20% of the repertoires of light orchestras and dance bands;

In this so-called jazz type repertoire, preference is to be given to compositions in a major key and to lyrics expressing joy in life rather than Jewishly gloomy lyrics

As to tempo, preference is also to be given to brisk compositions over slow ones so-called blues); however, the pace must not exceed a certain degree of allegro, commensurate with the Aryan sense of discipline and moderation. On no account will Negroid excesses in tempo (so-called hot jazz) or in solo performances (so-called breaks) be tolerated

So-called jazz compositions may contain at most 10% syncopation; the remainder must consist of a natural legato movement devoid of the hysterical rhythmic reverses characteristic of the barbarian races and conductive to dark instincts alien to the German people (so-called riffs)

Strictly prohibited is the use of instruments alien to the German spirit (so-called cowbells, flexatone, brushes, etc.) as well as all mutes which turn the noble sound of wind and brass instruments into a Jewish-Freemasonic yowl (so-called wa-wa, hat, etc.)

Also prohibited are so-called drum breaks longer than half a bar in four-quarter beat (except in stylized military marches)

The double bass must be played solely with the bow in so-called jazz compositions

Plucking of the strings is prohibited, since it is damaging to the instrument and detrimental to Aryan musicality; if a so-called pizzicato effect is absolutely desirable for the character of the composition, strict care must be taken lest the string be allowed to patter on the sordine, which is henceforth forbidden

Musicians are likewise forbidden to make vocal improvisations (so-called scat)

All light orchestras and dance bands are advised to restrict the use of saxophones of all keys and to substitute for them the violin-cello, the viola or possibly a suitable folk instrument.

So Jazz was banned. Unless… Unless you listened to the Nazi-approved, state-sponsored hot jazz band known as Charlie and His Orchestra. This was jazz for combat – a mutated, fenced in, politically driven Teutonic version of American culture that would win hearts and minds. In Hitler’s Very One Jazz Band, Mike Dash tells us how Nazi propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels attempted to harness jazz for Nazis ends:

Behind the scenes, though, Hitler’s propaganda chief was hatching a plot: music deemed unsuitable for decent Germans was to be harnessed to help drive the Nazi war effort. Here Goebbels’s catspaw was a jazz fanatic named Lutz “Stumpie” Templin, a fine tenor saxophonist who had led one of the best German swing bands before the war.

Templin was an equivocal character; no Nazi himself, he had nonetheless taken full advantage of the opportunities that opened under Hitler’s regime. As early as 1935, what would become the nucleus of the Lutz Templin Orchestra ousted its Jewish leader, James Kok, in order to secure a recording contract with Deutsche Grammophon. By the autumn of 1939, Templin’s reputation as a sax player and his links to the Nazis were strong enough for the Propaganda Ministry to turn to him when it took the decision to begin piping musical propaganda to British troops…

Lurking in the shadow of the new initiative were William Joyce, the notorious “Lord Haw Haw,” an Irish-American employed by Goebbels to broadcast propaganda to Britain, and Norman Baillie-Stewart, another fascist turncoat whose chief claim to fame was being the last Englishman to be imprisoned in the Tower of London. They provided ideas, and perhaps some lyrics, to a former civil servant named Karl “Charlie” Schwedler, the man hired to front the crack jazz musicians who made up Templin’s band…

The band’s ever-growing repertoire consisted mostly of dance standards, mixed with about 15 percent jazz… [But] American-born propaganda boss Edward Vieth Sittler admitted—“we cannot possibly perform this decadent ‘hot’ jazz as ‘well’ as Negroes and Jews.”

Maybe they’d have better luck with the words?

The first verse of each song would remain untouched, perhaps in the hope of luring in listeners. But the remainder of the lyrics would veer wildly into Nazi propaganda and boasts of Aryan supremacy. Charlie’s main themes were familiar ones: Germany was winning the war and Churchill was a drunken megalomaniac who hid in cellars at night to avoid German bombs (“The Germans are driving me crazy/I thought I had brains/But they shot down my planes”). Similarly, Roosevelt was a puppet of international banking cartels, and the entire Allied war effort was in the service of “the Jews.” For the most part, Schwedler’s songs interspersed virulent anti-Semitism with attempts to convince his audience that Nazi victory was inevitable. When Cole Porter’s classic “You’re the Top” got Charlie’s treatment, the revised lyrics emerged as “You’re the top/You’re a German flyer/You’re the top/You’re machine gun fire/You’re a U-boat chap/With a lot of pep/You’re grand,” and the lyrics for “I’ve Got a Pocketful of Dreams” became “I’m gonna save the world for Wall Street/Gonna fight for Russia, too/I’m fightin’ for democracy/I’m fightin’ for the Jew.”

What do you think of it so far? Says Skvorecky:

Well, some early American reviews of jazz sound very much like Soviet reviews. The difference is that a reviewer in America has no political power; it’s simply an opinion. In Czechoslovakia, on the other hand, a reviewer does have political power, and that’s the basic difference between totalitarianism and democracy. So though jazz in America may have aroused a lot of opposition initially, in a totalitarian state, such bias becomes law.

After leaving the ‘Club Americana’, a Saturday night jazz club open from midnight until 7 a.m., American troops and their girlfriends wait at Piccadilly Circus Station for the first train home, London, 25th November 1955.

After the Nazis, it was the turn of the Jazz Section of the Czech Musicians’ Union:

The Jazz Section was formed in 1971 as part of the government-approved Czechoslovak Musicians’ Union, and consisted of a group of jazz aficionados who sponsored lectures on jazz, staged concerts, and organized the international festival held once a year, the Prague Jazz Days. But as membership climbed into the thousands, and the Prague Jazz Days attracted thousands more potential supporters, the government saw a growing movement with a broad base of popular support and decided in 1984 to crack down on the Jazz Section. So they effectively banned it.

The Section itself has claimed that its activities aren’t counter to the principles of Marxism. They even built a monument to the United Nations in the fall of 1985, around which they planted “peace trees,” two of which were planted by Kurt Vonnegut and John Updike. But in spite of this gesture, the government cracked down again. In September, 1985, seven members of the Executive Committee of the Jazz Section, including its president, Karel Srp, were arrested in Prague and charged, according to the Communist Party press, with “unauthorized business activities.”

Skvorecky round up:

My father was a committed Democrat who mistrusted both the Nazis and the Communists, and was arrested by both. I grew up believing that the Communists were not much better than the Nazis. I had an aunt who was Jewish, and also a Communist. “You know,” my father used to say, “she’s really very nice, but she’s a Bolshevik.” She was very pretty, had red nails, smoked cigarettes from a long holder, and wore pants, which in those days was considered very radical. She disappeared in a Soviet labor camp, so when the war was over, I felt that the Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia was not much better—and possibly just as bad—as Nazi rule.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.