My childhood pleasure for eating sweets was sharply curtailed by the handiwork of my dentist. I thought he was an escaped Nazi hiding out at his practice in Edinburgh. He wore a starched white lab coat with a blue Paisley cravat tethered around his neck. When I entered his surgery (creaking bare floorboards, a former dining room, four large windows looking onto the terraced street below) I could almost hear his heels click with an Austrian formality. “Mac, so,” he would say–or at least I thought he said–as he hurriedly propelled me into the room with a very dead handshake.

He took a keen interest in my teeth and spent considerable time drilling holes and filling them. An anaesthetic injection was verboten. “You don’t need an injection, injections are vor babies. You are not a baby, hm?”

I was rather surprised as I never knew babies presented their gums for dental appraisal, so I suffered the pain in the misguided belief I was somehow a grown-up. “Don’t vince, girls vince. You are not a girl, hm?” He seemed to know what I was not rather than what I was.

I stopped eating sweets believing these sugary delights were the cause of all my dentist’s strenuous work. Every visit another couple of fillings, an extraction and more probing with a long sharp needle with which he worried holes in my molars. After one arduous session he rubbed his hands and said “Yes, you will be ready for dentures ven you’re twenty.” It was the seventies when plastic and Bri-Nylon were totems of the future. Then, fortunately, my parents moved house and we signed-up for another dental practice. Everything that I’d gone through was put into perspective when the new dentist looked at my mouth and said, “What the hell has been going on in here?”

I explained, half proud, that I was one day going to be ready dentures. He looked aghast. “We don’t do dentistry like that any more.” I never had another filling until my mid-twenties.

The young Roald Dahl seemingly avoided the hazards of such cruel dentistry and when he was a pupil at Repton school in England was one of the lucky few who were chosen to test new bars of chocolate, as he explained in his memoir Boy:

Every now and then, a plain grey cardboard box was dished out to each boy in our House, and this, believe it or not, was a present from the great chocolate manufacturers, Cadbury. Inside the box there were twelve bars of chocolate, all of different shapes, all with different fillings and all with numbers from one to twelve stamped on the chocolate underneath. Eleven of these bars were new inventions from the factory. The twelfth was the “control” bar, one that we all knew well, usually a Cadbury’s Coffee Cream bar. Also in the box was a sheet of paper with the numbers one to twelve on it as well as two blank columns, one for giving marks to each chocolate from nought to ten, and the other for

comments.All we were required to do in return for this splendid gift was to taste very carefully each bar of chocolate, give it marks and make an intelligent comment on why we liked it or disliked it.

It was a clever stunt. Cadbury’s were using some of the greatest chocolate-bar experts in the world to test out their new inventions. We were of a sensible age, between thirteen and eighteen, and we knew intimately every chocolate bar in existence, from the Milk Flake to the Lemon Marshmallow. Quite obviously our opinions on anything new would be valuable. All of us entered into this game with great gusto, sitting in our studies and nibbling each bar with the air of connoisseurs, giving our marks and making our comments. “Too subtle for the common palate,” was one note that I remember writing down.

This early experience inspired Dahl’s imagination:

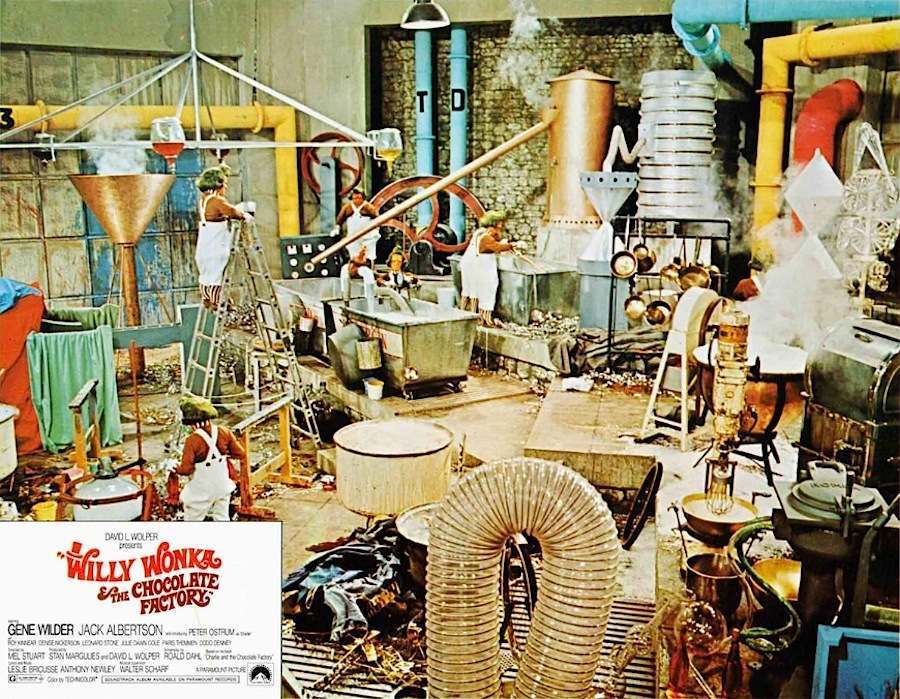

For me, the importance of all this was that I began to realise that the large chocolate companies actually did possess inventing rooms and they took their inventing very seriously. I used to picture a long white room like a laboratory with pots of chocolate and fudge and all sorts of other delicious fillings bubbling away on the stoves, while men and women in white coats moved between the bubbling pots, tasting and mixing and concocting their wonderful new inventions.

Which of course, some thirty-five years later, led Dahl to write Charlie and the Chocolate Factory.

Dahl loved sweets and enthused that the “seven glorious years, between 1930 and 1937” were when the greatest chocolate sweets were invented:

Cadburys made Dairy Milk in 1905

Cadburys made Bourneville Bar in 1910

Cadburys made Fruit and Nut in 1921…

1930 the Crunchie, the Whole Nut Bar

’32 Mars (600 million a year)”

’33 Black Magic

’34 Tiffin, Caramello

’35 Aero

’36 Maltesers… Quality Street

’37 Another great year, Kit Kat, Rollo, Smarties…

A scan of a cross section of a Kit-Kat.

Dahl thought these dates were far more relevant to a child’s life than any dry facts about monarchy kept in history books:

“Don’t bother with the Kings and Queens of England. All of you should learn these dates instead. Perhaps the Headmistress will see from now on that it becomes part of the major teaching in this school.”

When he had an idea for a story, Dahl had to write it down straight away or it would be lost for ever. One note read:

What about a chocolate factory that makes fantastic and marvellous things–with a crazy man running it?

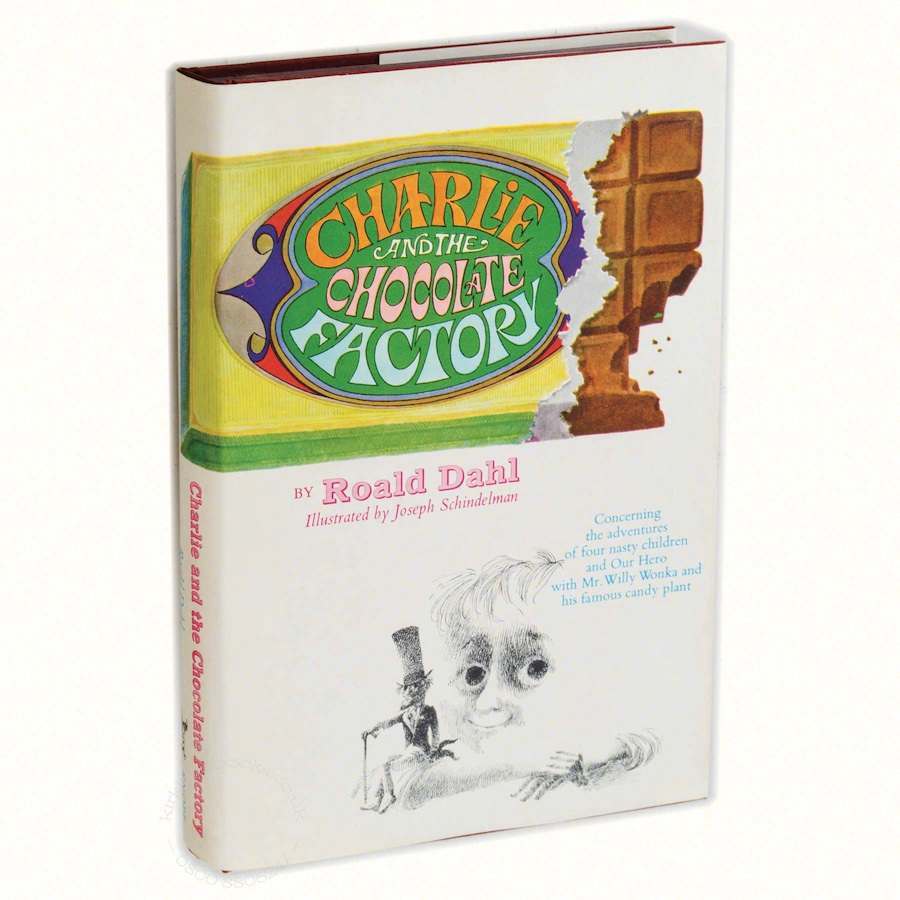

This became Charlie and the Chocolate Factory which was published fifty years ago on 30th December 1964. Dahl was then a famous writer of twisted short tales and had published only one children’s books James and the Giant Peach, which had met with indifference from both critics and readers alike. However, Charlie and the wonderfully eccentric Willy Wonka was about to change all that.

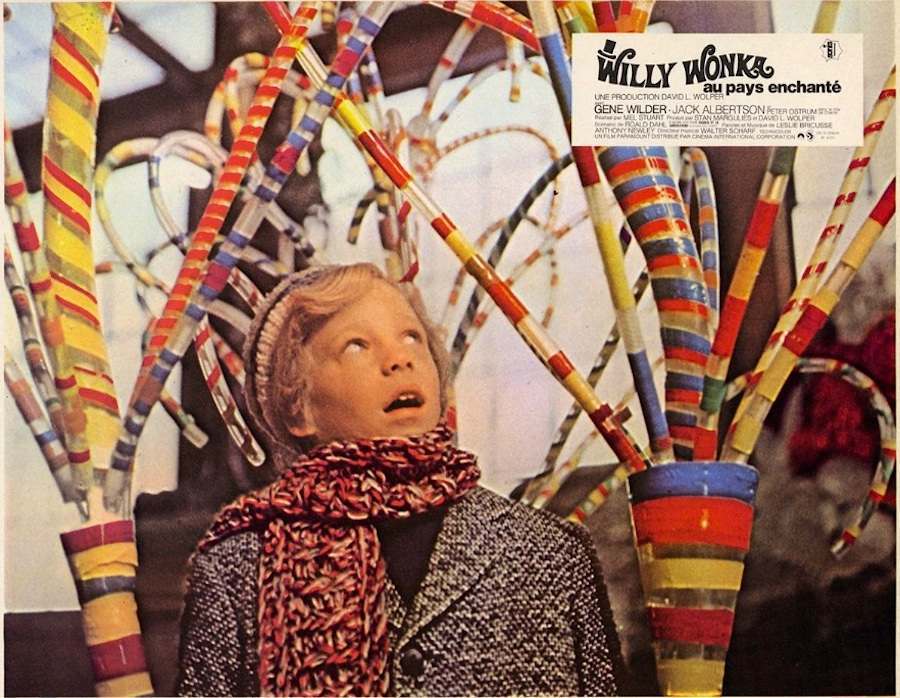

Charlie and the Chocolate Factory tells the story of a young, poor boy called Charlie who finds a winning “golden ticket” inside one of Willy Wonka famous chocolate bars. This ticket entitles Charlie (and the other winners) to a trip around Wonka’s extraordinary factory. The story changed over its six drafts from a detective story to a more fantastical tale and had several character changes–originally there were no Oompa-Loompas and no Grandpa Joe, the grown-up who accompanied Charlie on his visit to the factory. The book’s writing was overshadowed by two tragic events in Dahl’s life: a car accident involving his son Theo that left him needing a shunt (co-designed by Dahl) to relieve pressure on his brain; and the tragic death of his daughter Olivia that devastated him. The horrors of these events were filtered into the grotesque and surreal demise of some of the children in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory who were apparently, as biographer Donald Sturrock notes: “juiced, stretched, minced, flushed down a rubbish chute or cooked in a fudge-boiler”. But it’s all just fun and games as Wonka ultimately explains:

“I run a chocolate factory not a butcher’s shop.”

Dahl had intended Charlie to be “a negro child” which was somehow lost in the rewrites and in the turmoil of his personal life–a change that proved ironic when the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) took great offence over the book.

James and the Giant Peach had sold just over two thousand copies and left Dahl wondering if there was any point to writing any more children’s books. However, he was committed to writing the tale and when eventually published Charlie launched Dahl’s career as a hugely successful children’s author.

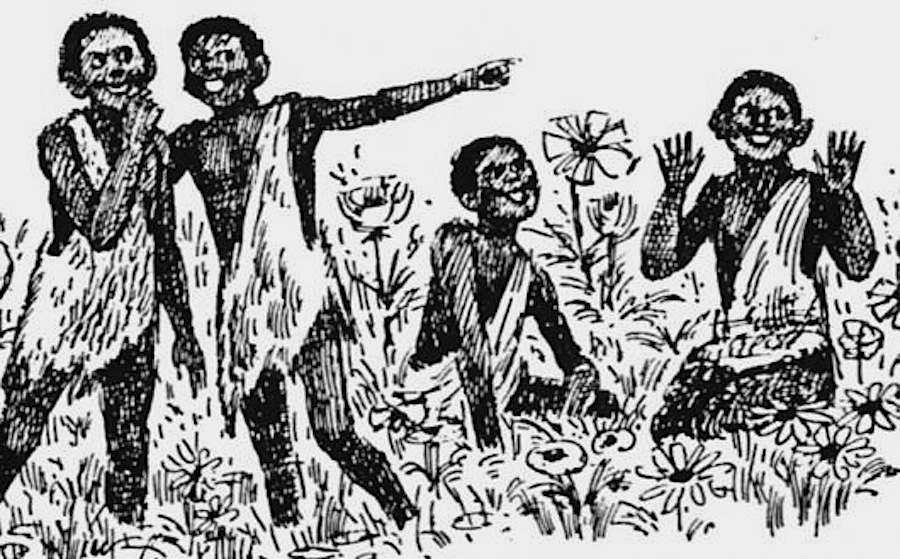

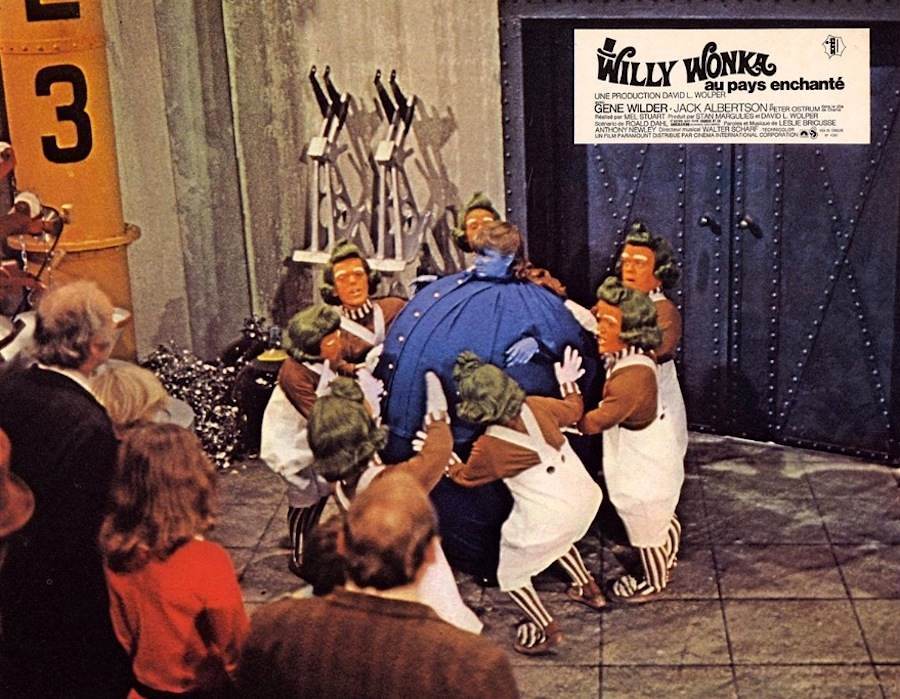

The book was optioned and a movie planned, which when the NAACP objected to Charlie and the Chocolate Factory on grounds the book was racist. This claims of racism were based on Dahl’s description of Wonka’s factory staff, the Oompa-Loompas, who were portrayed as African Pygmies “from the very deepest and darkest part of the jungle where no white man had ever been before”.

The offending illustration of the Oompa-Loompas.

Dahl was perturbed by the accusation, as Donald Sturrock writes in his biography on Dahl Storyteller:

For Roald, this conclusion came as a complete shock. Not only had he never intended this fanciful detail to cause offence, he had also quite failed to appreciate fully the ferocity of the social tide that eddied around almost every public project within in the United States at that time. Civil rights were a burning issue, the Black Panther movement was at its height, and Martin Luther King Jr., had recently been assassinated. For the NAACP, the Oompa-Loompas seemed clearly to reinforce a stereotype of slavery that American blacks were trying to overcome. Exaggerated rumours quickly spread that the organization would picket any cinema which screened the movie and that even the word “chocolate” in the title implied racist overtones. The producers were put under pressure to change both the nature of the Oompa-Loompas and the title of the film.

When respected author and playwright Lillian Hellman weighed in on Dahl’s side by writing a letter supporting Charlie, the NAACP replied:

“The objection to the title ‘Charlie and the Chocolate Factory’ is simply that the NAACP doesn’t approve of the book, and therefore doesn’t want the film to encourage sales of the book. The solution is to make the Oompa-Loompas white and to make the film under a different title.”

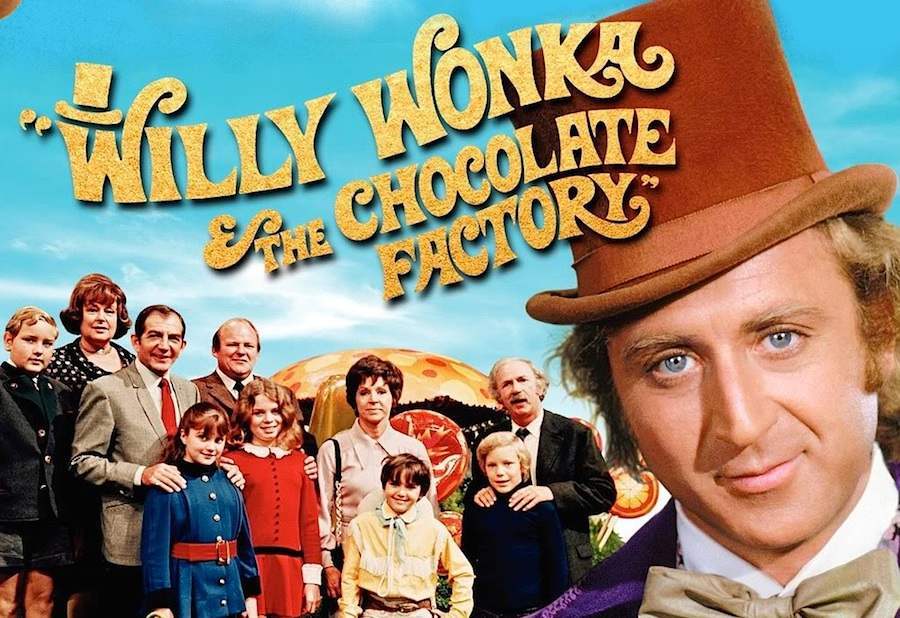

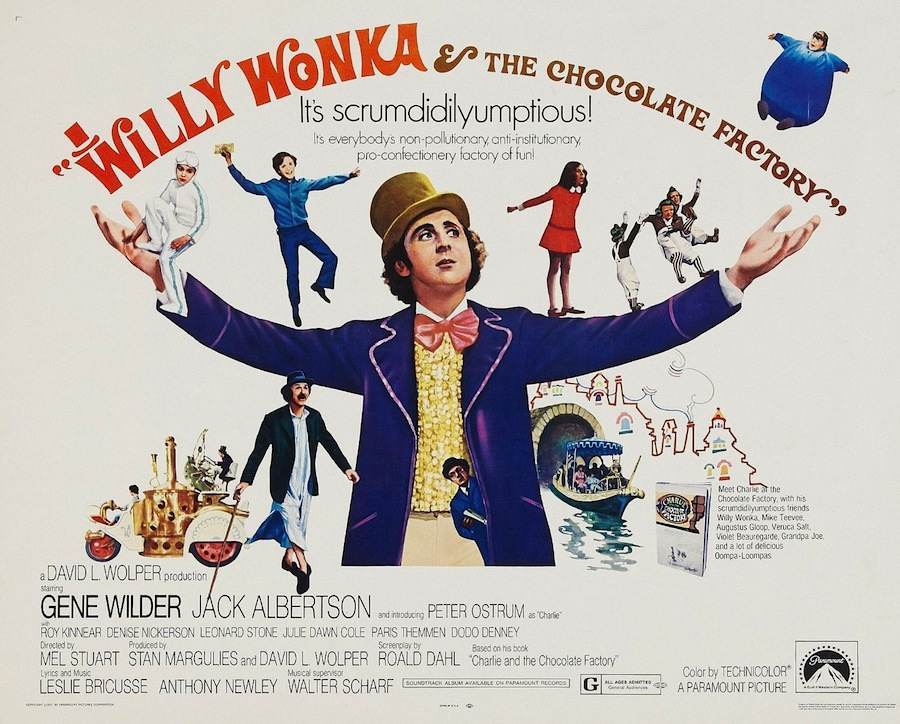

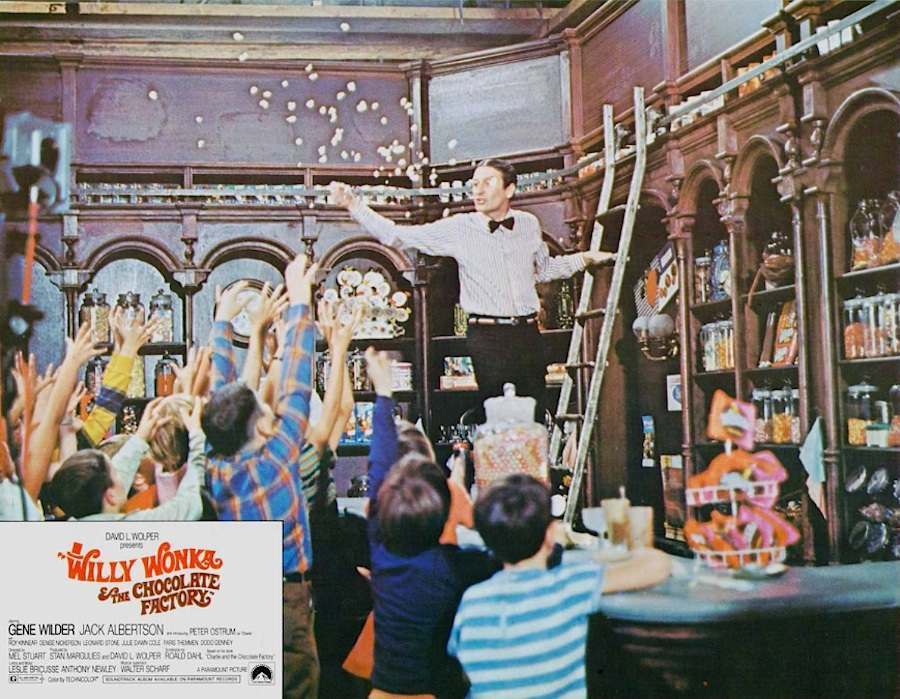

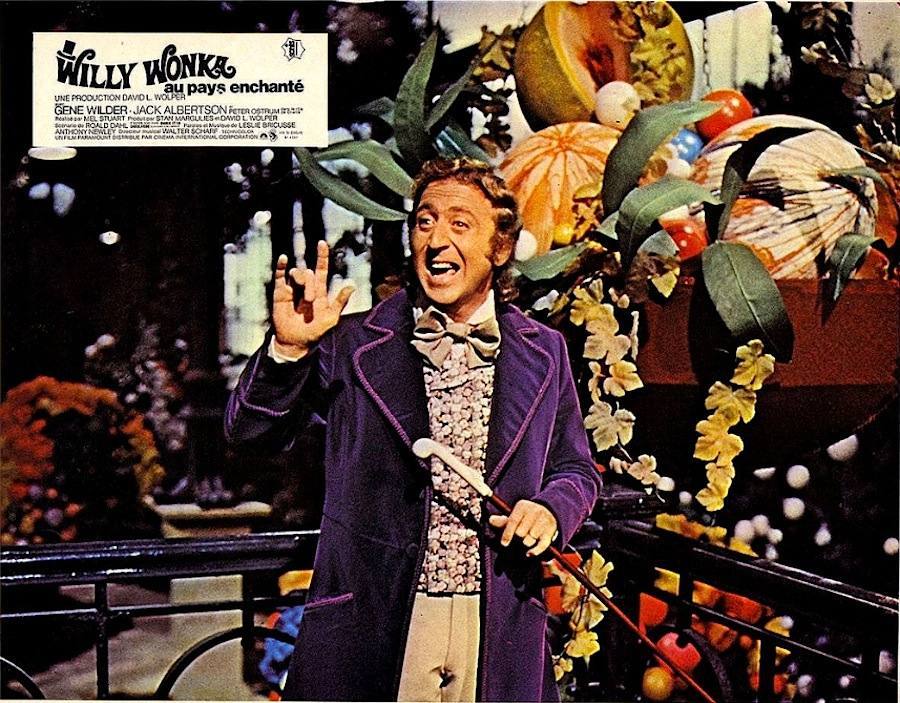

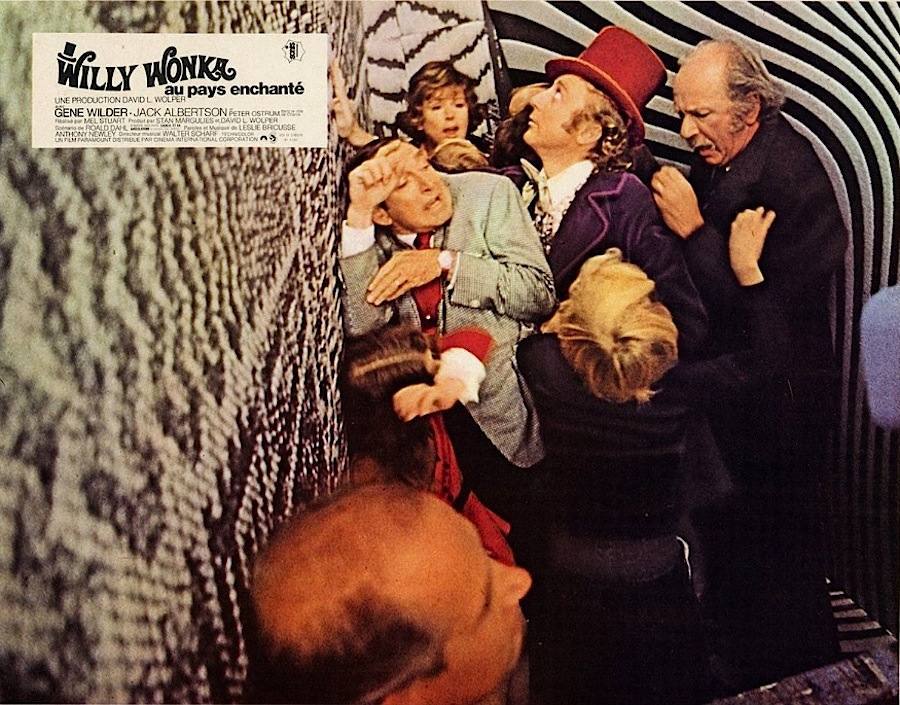

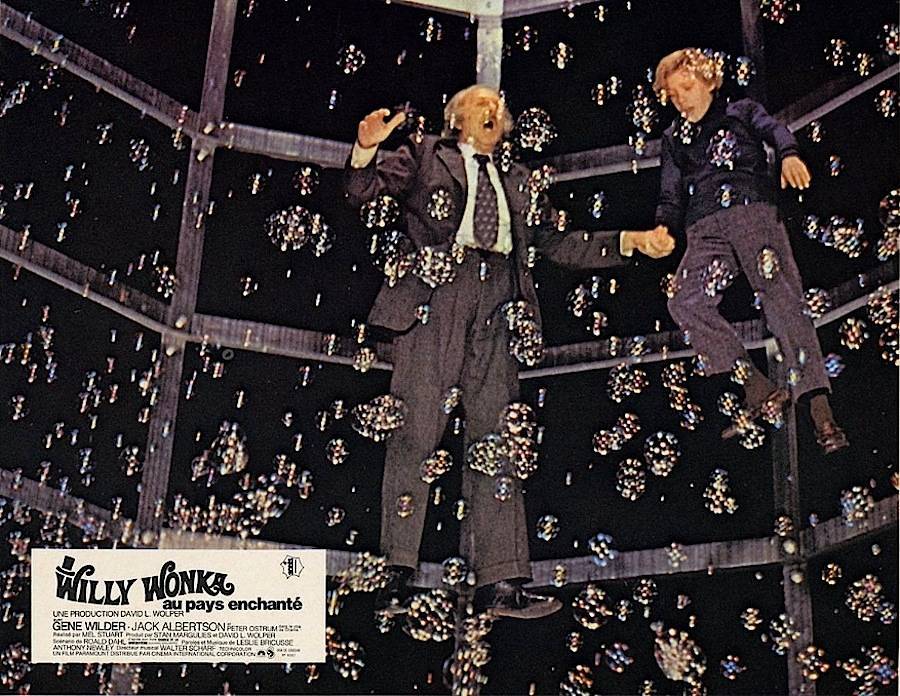

Gene Wilder as Willy Wonka with the changed Oompa-Loompas.

Dahl was more than willing to change the colour of the Oompa-Loompas but felt “shattered” by the NAACP’s attitude and couldn’t understand why they thought it a “terrible dastardly anti-negro book.”

In a letter to publisher Alfred Knopf, he described what happened:

The book is banned by the NAACP. They thought I was writing a subtle anti-negro manual. But such a thing had never crossed my mind.

He also failed to mention that the positive role model Charlie had originally been black.

The Oompa-Loompas were eventually turned green-haired and orange-skinned, and the film title was changed to Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory.

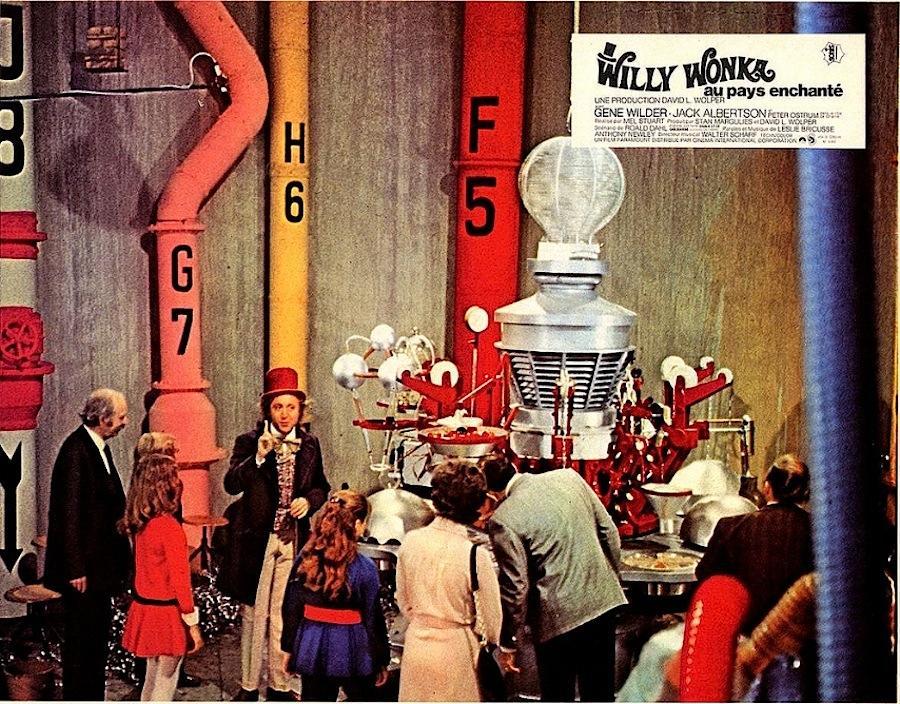

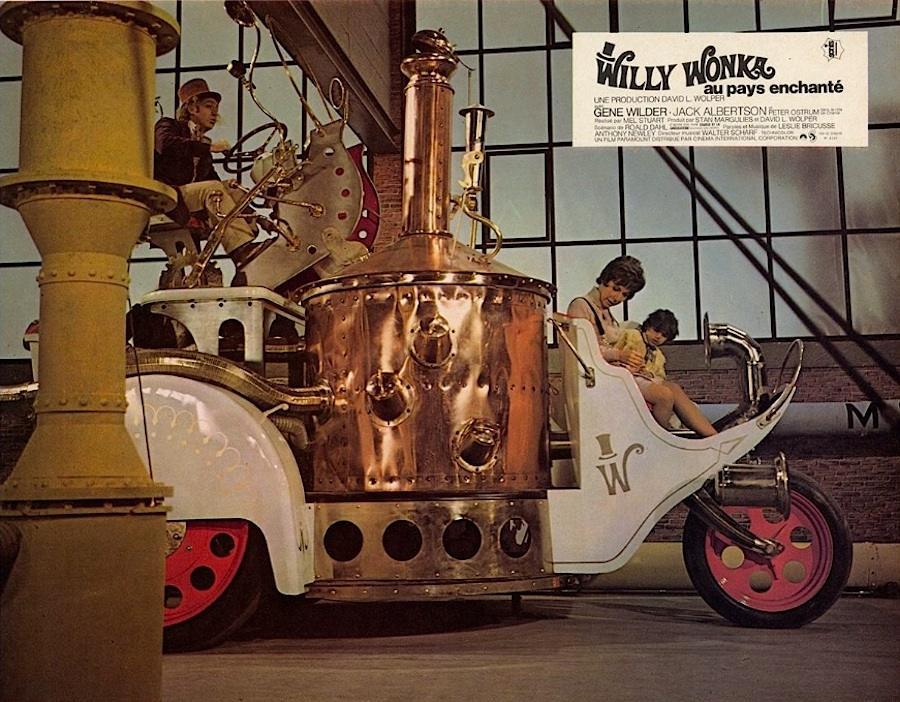

Though Dahl had been paid $300,000 for writing the screenplay, he never liked the movie–he tolerated it. He admitted there were”many good things” in the film, but he didn’t like how his script had lost some of its bite and had been tinkered with by David Seltzer, the screenwriter director Mel Stuart had hired. As for the director, Dahl thought Stuart had “no talent or flair whatsoever”. He was further irked that his suggestion of Spike Milligan for the role of Wonka had been ignored, as had Peter Sellers who begged Dahl to play the part. Both were knocked back in favour of Gene Wilder–who Dahl thought too “bouncy” and “pretentious”.

It became so bad that Dahl considered running his own advertising campaign to denounce the movie. But this never came to anything as the film quickly became a hit and then a children’s movie classic and Dahl mellowed as the Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory brought greater attention to his work and meaning greater sales.

The book made Roald Dahl the bête noire of librarians who, though they had never complained about Charlie before the controversy with the NAACP, eagerly searched his books for any possible offence. The experience nearly made Dahl give up writing children’s stories, but his passion for storytelling proved greater than any personal hurt, and he followed Charlie and the Chocolate Factory with Fantastic Mr. Fox in 1970. However, having had a short and highly successful career as a screenwriter (the Bond movie You Only Live Twice, and the children’s musical Chitty Chitty Bang Bang) he never wrote another film script after Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory.

Would you like to support Flashbak?

Please consider making a donation to our site. We don't want to rely on ads to bring you the best of visual culture. You can also support us by signing up to our Mailing List. And you can also follow us on Facebook, Instagram and Twitter. For great art and culture delivered to your door, visit our shop.